Scholar Fridays is a weekly series on Bearings Online where we feature 2017-18 Resident Scholars. Susan Sink recently interviewed Robert (Bob) Kitchen, who spent the spring semester at the Collegeville Institute as a Resident Scholar. Kitchen is a retired minister and teacher from Regina, Saskatchewan. During his residency, he worked on his project titled “Resurrecting the Library of Mar Behnam Monastery, Mosul.” To view previous Scholar Friday interviews, click here.

Tell us about your project.

Robert (Bob) Kitchen

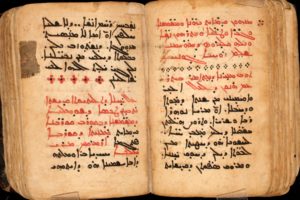

I am translating and doing a commentary on a Syriac “monastic anthology” — a selection of stories and homilies on the spiritual life — from the library of Mar Behnam Monastery, near Mosul, Iraq. The monastery was destroyed by ISIS, yet the library was successfully hidden and protected by a monk. The entire library was photo-digitized by the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library (HMML) several years before. The manuscript is dated 1231 C.E., but the texts are generally from the 5th-7th centuries. The texts themselves are not new to scholars, but it is how they were put together for the benefit of a monk’s reading and the development of his spiritual life that is the intriguing and creative element in this manuscript.

You are a joint fellow with the Collegeville Institute and Hill Museum & Manuscript Library. That’s a lot of scholars to be around! How do those communities support you in your work and how have they supported your work in the past?

When you come to places like the Collegeville Institute and HMML, you never find someone working exactly on what you are studying, and that’s actually good. Listening to other scholars’ investigations and frustrations enriches me and presents me with other directions and perspectives to look again at what I am doing. Plus, it is more fun to be with others who are serious about their projects, and it’s simply contagious.

Has your scholarship been affected or have you been affected by the wars tearing apart Syria? How would you invite us to think about Syria as Christians?

My wife and I lived in Södertälje, Sweden, for five months where I taught Syriac studies at Sankt Ignatios Theological Seminary. During the past 50 years, Södertälje has become home to the largest concentration of Syriac Christians outside the Near East. Most of the students were born in Sweden to families who had immigrated from Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Iran, and Turkey, in most instances because of prejudice, persecution, violence, and war in their homelands. They have created a strong community that has transformed this small Swedish city.

Syriac is the Aramaic dialect closest to the language that Jesus spoke, and their history and literature developed in parallel with the Greek and Latin traditions – although we in the West have forgotten that they existed, even though they have been Christians long before most of us. The sophistication of their theology and the beauty of their poetry and Biblical interpretation are things from which we should no longer deprive ourselves.

You are no stranger to both the Collegeville Institute and HMML. How has your experience of these institutions since your first visit?

I first came to HMML in 1988/89 and have visited many times to do research. I did not get an opportunity to be a resident at the Collegeville Institute until 2014, but many good things are worth waiting for. Both institutions have provided a truly gracious hospitality and encouragement that has made scholarship a pleasure, especially located in the physical surroundings of Saint John’s and Saint John’s Abbey. With HMML, I have made the transition from microfilm to digitization, and now the superb renovations to the physical space at HMML. The Collegeville Institute remains a place where one can become different and spiritually renovated.

I see you were a United Church of Christ pastor in International Falls, Minnesota, one of the truly coldest places on earth. What are your observations about the rural church in North America?

There are colder places than International Falls, but we haven’t lived there yet! Faith United Church of Christ probably should not be called “rural” – a “severely isolated” small town might be more fitting. Nevertheless, it shares some of the same problems as the rural churches in which economics and migration have slowly squeezed the critical mass from small communities. Where faithful and realistic leadership endures in these churches, the Christian faith continues to become flesh daily. All too often the Church has allowed these congregations to atrophy through neglect of experienced leadership and by denominational leaders not visiting and acknowledging their contributions.

What has been your greatest ecumenical moment while in residence at the Collegeville Institute?

Meryem Ana Kilisesi in Diyarbakir, Turkey, DIYR 202, ff. 76v-77r. Image courtesy of the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library, Saint John’s University, Minnesota. Image source.

In January 2014 when I arrived at HMML and the Collegeville Institute for the semester, there in the next carrel was Pѐre Roger Akhrass, a Syriac Orthodox monk, priest, and scholar from Saint Aphrem’s Monastery in Ma’aret Saydnaya, near Damascus, Syria, the Patriarchal Seminary. Besides helping each other in Syriac matters, we did a lot of social things together and came to learn a lot about each other’s traditions, despite the fact that we were both “heretics” to each other according to those traditions! During our time in Collegeville, the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch died and we watched the funeral together online and the subsequent election of the new Patriarch. I was asked later to translate into English several of the prayers for the ordination of the new Patriarch, Mor Ignatius Aphrem II, a very ecumenical event for me, and possibly for the Syriac Orthodox if they recognized it. Since then Roger and I have worked together on several publications and keep in close contact.

If you could visit any historical church community anywhere in the world, which would it be and when? What would you hope to learn from them?

That is a question that sets the imagination in motion. I can think of three places and times. First, the Syriac churches in Nisibis and Edessa (both now in modern Turkey) where Ephrem directed the choir of women to sing the hymns he had composed, mid-4th century. Second, the First Church of Christ, Northampton, Massachusetts, in the early 1740s when Jonathan Edwards helped lead the First Great Awakening. Finally, the little Reformed congregation of Safenwil in the Aargau region of northern Switzerland where Karl Barth was the pastor during the years of World War I and following. All three are where quiet but important innovations were introduced, all involving the spoken Word.

Like this post? Subscribe to have new posts sent to you by email the same day they are posted.

Thank you for this enjoyable read. “…and their history and literature developed in parallel with the Greek and Latin traditions – although we in the West have forgotten that they existed…” As someone who has an MA in “Western” medieval art history, the recent reports on the rescue of manuscripts from Oriental Churches has piqued my interest in these manuscripts as expressions of art and knowledge. I do not recall any mention by any of my professors about connectivity and the circulation of knowledge between Western and Oriental church manuscripts, and for that matter, other forms of artistic expressions. Is there a lacuna that has yet to be addressed or am I just ignorant about such connectivities? It is now prevalent to read inter-cultural exchange between Islamic and Christian traditions in medieval art histories, but I don’t manage to recall discussions of Oriental-Western exchange or connectivity.

For those interested, you can view the entire manuscript discussed in this article on vHMML at: https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/124492