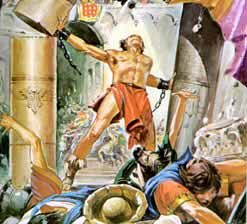

Not long ago my family and I stumbled into the Sunday morning worship service of a moderate mainline congregation. We soon found ourselves perched in front of a jazz-handed youth choir singing “God Brings Down the House” as the grand finale of a musical about the story of Samson. Listening to the choreographed Samson ditties, my husband leaned over and whispered, “Is this really how we want to package the acts of an ancient equivalent of a suicide bomber?”

Undoubtedly, no one in the sanctuary that day would invoke the Samson story to justify terrorism in the contemporary setting. Like many North American Christians, they were used to hearing this story interpreted as a fable about personal piety. If we turn our backs on God, God may take away our strength. If we return to God, our strength will be restored. God “bringing down the house” was similarly metaphorical: God destroys evil and vindicates righteousness. The Samson story presents an opportunity to generate a steady stream of haircut jokes in order to teach lessons about temptation. The uncomfortable implications of the story about God’s vindictiveness or capriciousness—at least from the Philistine point of view—are conveniently omitted.

Undoubtedly, no one in the sanctuary that day would invoke the Samson story to justify terrorism in the contemporary setting. Like many North American Christians, they were used to hearing this story interpreted as a fable about personal piety. If we turn our backs on God, God may take away our strength. If we return to God, our strength will be restored. God “bringing down the house” was similarly metaphorical: God destroys evil and vindicates righteousness. The Samson story presents an opportunity to generate a steady stream of haircut jokes in order to teach lessons about temptation. The uncomfortable implications of the story about God’s vindictiveness or capriciousness—at least from the Philistine point of view—are conveniently omitted.

As precocious Sunday school students have learned the hard way, asking tough questions about Old Testament representations of divine activity is taboo in many Christian circles—especially if those questions are voiced publicly. Recently, Eric Seibert, a Brethren in Christ minister and professor of Old Testament at Messiah College, made waves on cyberspace by publishing a series of blog posts about violent portrayals of God in the Bible.

Seibert, who maintains that the Bible should never be used to cause harm and that “not everything in the ‘good book’ is either good, or good for us,” was promptly chastised on the blogosphere for his posts. As Fred Clark pointed out, evangelical gatekeepers—perceiving Siebert’s questions about Old Testament portrayals of God as threatening or irreverent—were quick to challenge Seibert’s orthodoxy.

How God acts in the world is an old theological problem, but the responses to Seibert, and to Samson, make me wonder how rank-and-file parishioners across the spectrum of American Christianity do in fact conceptualize the role of God in human affairs—both historically and in today’s world. I doubt that many Catholics, moderate evangelicals, or mainline Christians would argue that God sanctions genocide, slavery, terrorism, or patriarchy, as common representations of divine activity in the Old Testament would suggest. They would also hesitate to attribute natural disasters like hurricanes and floods directly to the hand of providence. Still, many of these Christians would be uncomfortable with Seibert’s suggestion that “we need to learn to have problems with the Bible” and its sometimes objectionable accounts of God. And there must be a healthy market for church musicals based on the Old Testament’s violent portrayals of God, even in mainline churches, or the Christian publishing world would stop producing the scores.

How can these seeming contradictions be explained? Do people fail to think about them, willfully suppress them, or soften them through hermeneutical devises? Do they envision God acting differently in ancient times from how God acts today? Are they more comfortable having problems with God than having problems with the Bible?

Each of these lines of inquiry may offer a partial explanation for how Christians can simultaneously repudiate contemporary appeals to divinely sanctioned violence and still take Old Testament accounts of God’s activity at face value. But for those Christians who reject each of these strategies, what are the alternatives? Particularly in our collective lives of faith, how can we at once love the Bible and “learn to have problems” with it, as Seibert suggests?

If you are part of a community of faith who wrestles with these questions, we’d love to hear what you do. If Samson musicals featuring a God who “brings down the house” are not part of your liturgical life, how do you deal with troubling biblical portrayals of God? Do you alter, skip, or gloss certain Lectionary passages in your collective worship? Which Old Testament stories do you share with children, and how are they presented? How does your community at once love the Bible and have problems with it?

Like this post? Subscribe to have new posts sent to you by email the same day they are posted.

Hi- Do you know what book this image is from? I had a children’s bible as a child and this image was in it. I want to buy it for my own kids, but can’t remember the title. Thanks!

I’m sorry, but this was so long ago, we have no record of where the image came from. We are always conscious of running copyright-free images, so perhaps try wikimedia? But the staff is not the same as in 2013 and it’s impossible to know the source!