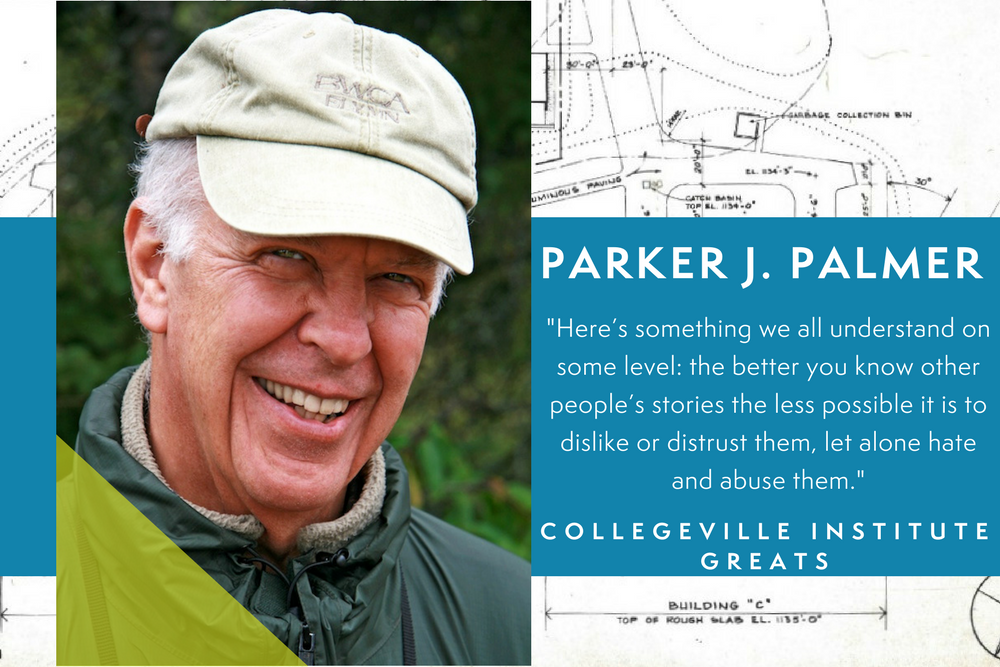

As we celebrate our 50th Anniversary, Bearings Online is highlighting profiles of persons closely associated with Collegeville Institute’s history—that great cloud of witnesses who have accompanied us since 1967, and will journey with us into the future. This is part two of an interview with Parker J. Palmer, which was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2010 edition of Bearings Magazine.

Click here to read part one of the interview.

The kind of storytelling you’re talking about allows people to see one another as human beings and individuals rather than as stereotypes.

Absolutely. Here’s something we all understand on some level: the better you know other people’s stories the less possible it is to dislike or distrust them, let alone hate and abuse them. The kind of story telling I’m talking about can happen in classrooms. It can happen in congregations. We can teach people that it’s possible to get the news from sources other than the media—we can get the news from the human heart. We can get the news from each other. We can get it from poetry. We can get it from prayer. We can get it from great literature. It’s news of a deeper, more hopeful, and more lasting sort than news of some preacher in Florida who wants to burn Qur’ans.

When we start by debating our positions we often end up at a dead end.

When we start by debating our positions we often end up at a dead end. If somebody believes that Scripture was literally dictated by God with no human mediation; that there is a clear unambiguous meaning to every passage of scripture; and that everything in it applies with as much force today as it did when it was written, then that person and I will simply go around in circles if we debate one another. But I’m betting that the two of us would have a lot to talk about regarding the life journey that has shaped our religious convictions— and that we would arrive at a deeper understanding of one another if we could have that conversation. In many ways the question is, “What are we in this conversation for?” Is our primary motivation to change each other’s minds? If that’s the case, I’m generally not interested, because in most cases I don’t think that’s going to happen. However, if we are in conversation to discover whether we have a human bond on which we might build something larger—including some sort of personal transformation—that’s a conversation I’d really like to join.

So you would have no hesitation about engaging in such conversations with a self-designated fundamentalist?

I’d surely want to try. In a society in which fundamentalism is a powerful force, it’s essential to do so. I suspect that in an extended conversation a fundamentalist believer and I might find that we share a broken heartedness over the conditions of modern life. We might grieve the crudity of modern culture, as in the way sexuality is used in an exploitative manner in advertising and elsewhere. We might share grief over our culture’s indifference to suffering and death. Might it be possible for us to stand together on this small but important patch of ground called the shared experience of a broken heart and see if there is something more for us to talk about? It would be a tremendous and tragic irony if those of us who claim to be open-minded and open-hearted— and say we are eager to engage “the other”— fail to try to be in conversation with that form of otherness we liberals call fundamentalism.

I’m advocating what I call “standing and acting in the tragic gap” between reality and possibility.

My liberal friends say that we can’t be in dialogue with those who don’t want to be in dialogue with us. Perhaps. But I don’t think we’ll know that for certain until those of us who are not fundamentalists make a sustained effort to open our hearts to those who are. Here I’m advocating what I call “standing and acting in the tragic gap” between reality and possibility. Do I believe that fundamentalist believers are going to accept my vision for American society any time soon? No. Do I believe it’s possible for fundamentalists and non-fundamentalists to live together in a way that strengthens our common democratic society? Yes. But only if we learn to hold tensions between what is and what could be without trying to resolve that tension prematurely. To go back to Terry Tempest Williams, can fundamentalists and non-fundamentalists trust one another to pursue life together in a democracy, in a state of tension, despite uncertainty and pain? And can that trust begin where it must, with us, with me?

I’m sure some readers might find your views on healing the body politic somewhat quixotic. Millions upon millions of dollars are spent each year to move American politics this way or that and you’re proposing that people talk with one another.

Guilty as charged, and proud of it! I’m in good company, I think. Abraham Lincoln appealed to “the better angels of our nature” and his appeal was genuine and deeply felt. I’m arguing for pretty much the same thing. Americans need to pursue what I call “soul work”— work on our inner lives. If we write off soul work as nothing more than dewy-eyed romanticism we ignore not only human history but significant objective data as well. To cite one example, two highly regarded scholars, Anthony Bryk and Barbara Schneider, have demonstrated that in schools with high degrees of relational trust between administrators, teachers and parents, students will do better academically than students in schools where relational trust is low. They found relational trust more important to learning outcomes than money, curriculum, teaching technique, etc. (Their book is called Trust in Schools.) So what makes it possible to develop relational trust? Soul work. I mean things like getting the ego under control, learning forgiveness, learning how to deal with anger. These scholars present us with compelling evidence that relational trust makes a significant difference in institutions as complex— and in some cases as dysfunctional—as public schools. If we want to restore and strengthen our democratic institutions we need to take soul work seriously, the kind that makes relational trust possible.

Let me give you another example of the power of “soul.” One of my favorite stories along these lines is the story of John Woolman, a Quaker tailor who—100 years before the Civil War—said to his Quaker confreres in colonial New Jersey, “It has been revealed to me that God wants us to free our slaves.” To make a long story short, his fellow Quakers—who made decisions by consensus, not by majority rule—wrestled and wrestled with Woolman’s call, and could not reach consensus. But neither could they dismiss the issue. They couldn’t simply take a vote on it and get it over with. So they said to Woolman, “We don’t agree with you, but we do not doubt your integrity when it comes to listening for God’s will. So we will help support your family while you travel among us preaching your word, and we will see what happens.” Now that’s relational trust! For the next 20 years Woolman traveled up and down the east coast until the Quakers finally reached consensus on freeing their slaves. They were the first religious community in the United States to do so—and they did it 80 years before the Civil War.

Let me give you another example of the power of “soul.” One of my favorite stories along these lines is the story of John Woolman, a Quaker tailor who—100 years before the Civil War—said to his Quaker confreres in colonial New Jersey, “It has been revealed to me that God wants us to free our slaves.” To make a long story short, his fellow Quakers—who made decisions by consensus, not by majority rule—wrestled and wrestled with Woolman’s call, and could not reach consensus. But neither could they dismiss the issue. They couldn’t simply take a vote on it and get it over with. So they said to Woolman, “We don’t agree with you, but we do not doubt your integrity when it comes to listening for God’s will. So we will help support your family while you travel among us preaching your word, and we will see what happens.” Now that’s relational trust! For the next 20 years Woolman traveled up and down the east coast until the Quakers finally reached consensus on freeing their slaves. They were the first religious community in the United States to do so—and they did it 80 years before the Civil War.

When people say that soul work and consensus sound nice but are inefficient, I like to point to this example. Quakers acted on what is arguably the greatest moral issue of American history—they ended slavery in their community, without violence—and they did it 80 years before the Civil War! What’s “inefficient” about that? And, I should add, this is also a good example of work on the pre-political level moving up to the political level in a very powerful way—because in 1787, Quakers petitioned the U.S. Congress to correct the “complicated evils” and “unrighteous commerce” created by the enslavement of human beings. (You can see the document online at the National Archives site.)

In the these pre-political settings there are enormous opportunities to help us develop democratic habits of the heart.

I don’t have any fantasy that we’re going to make decisions by consensus in national, state or local politics, or that somehow we’re all magically going to just “get along.” On the level of national politics, we’re always going to have to vote up or down in terms of electing people, passing bond issues and so forth. I do believe, however, that in the these pre-political settings (schools, colleges and universities, churches and other voluntary associations) there are enormous opportunities to help us develop democratic habits of the heart that can lead us to take each other seriously—to listen to one another not as adversaries but as persons— which is what is at the spiritual heart of consensual decision-making.

Woolman’s example would seem to speak to the church as well as the body politic.

It grieves me when I see churches make decisions by majority rule. We take our short attention spans into a meeting, start talking about some issue, and within 30 minutes we realize we’re pretty badly divided on the matter. But somebody does a silent head count and figures out that if they call the question now they can win this vote for their side. So we call the question, we vote—and we get a decision made “efficiently” without ever counting the cost. The cost, of course, is an alienated minority— and the development of a habit of the heart that says we don’t need to listen to each other very deeply or very long. We only need to figure out where power lies and use it to our advantage.

The purpose of decision-making in a church is not to get a decision made but to up build the Body of Christ.

That’s not good citizenship. And that’s certainly not good church. I’ve always said that the purpose of decision-making in a church is not to get a decision made but to build up the Body of Christ. I deeply believe that. I also believe that if you build up the Body of Christ you’re eventually going to make a better decision about whatever is at hand. Can we live with the tension between the real and the possible for as long as it takes to break open hearts so that a new creative synthesis can be reached between quite divergent positions? That’s a question for churches and for anyone who cares about American democracy.

Click here to read part one of the interview.

Like this post? Subscribe to have new posts sent to you by email the same day they are posted.

Leave a Reply