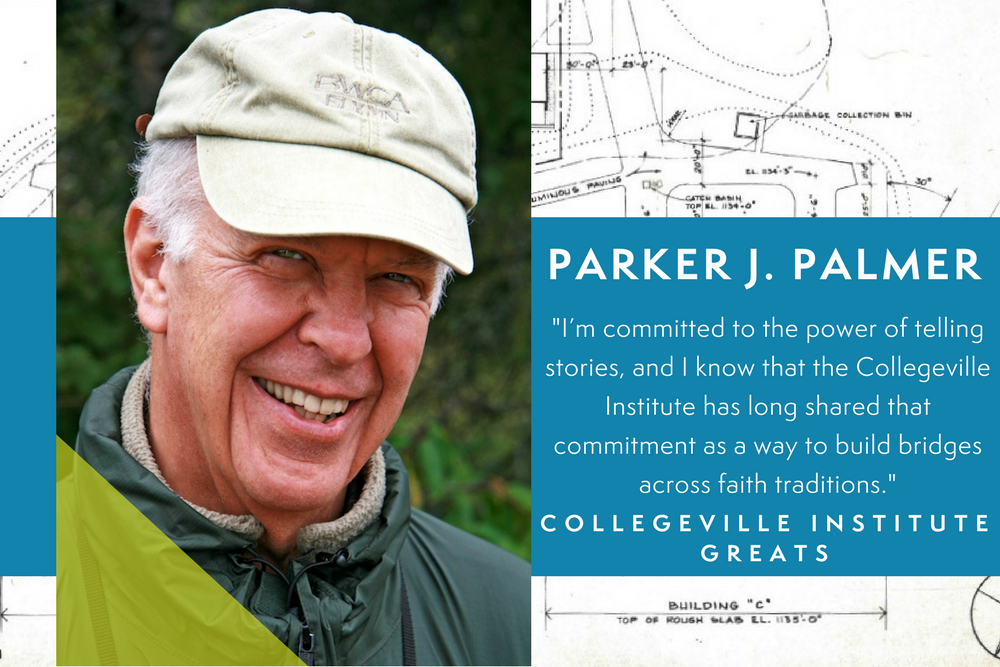

As we celebrate our 50th Anniversary, Bearings Online is highlighting profiles of persons closely associated with Collegeville Institute’s history—that great cloud of witnesses who have accompanied us since 1967, and will journey with us into the future.

Parker J. Palmer, best-selling author and educator, is founder and senior partner of the Center for Courage and Renewal. The Center’s mission is to nurture personal and professional integrity, and the courage to act on it. As a gifted teacher, speaker, and writer, Palmer is widely recognized as a singular voice in American letters whose work illuminates, as Henri Nouwen once said, “the relations between interior search and public involvement.” His influential books have unpacked key notions around themes involving personal wholeness, public life, community, teaching and education, the spirituality of work, and vocation.

During his time as a Resident Scholar at the Collegeville Institute (1980-81), Palmer wrote a first draft of To Know As We Are Known.

During his time as a Resident Scholar at the Collegeville Institute (1980-81), Palmer completed his book The Company of Strangers: Christians and the Renewal of America’s Public Life, and wrote a first draft of To Know As We Are Known: A Spirituality of Education. Since that time, he has authored numerous books and articles, including Let Your Life Speak: Listening for the Voice of Vocation. He received his B.A. in philosophy and sociology from Carleton College; and his M.A. and Ph.D. from the University of California at Berkeley. Parker was named recipient of the 2010 William Rainey Harper Award, “given to outstanding leaders whose work in other fields has had profound impact upon religious education.” Named after the first president of the University of Chicago, the award has been given only ten times since its establishment in 1970 by the Religious Education Association. Previous recipients include Marshall McLuhan, Elie Wiesel, Margaret Mead and Paulo Freire. Palmer and his wife Sharon live in Madison, Wisconsin.

The following interview with Palmer was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2010 edition of Bearings Magazine. At the time, Palmer was about to publish his book Healing the Heart of Democracy: The Courage to Create a Politics Worthy of the Human Spirit (Jossey-Bass, 2011). Though the political landscape has shifted dramatically since 2010, Palmer’s connection between “soul work” and politics has never felt more timely. The interview, originally titled “The Heart of Politics,” has been edited for length and divided into two parts. Click here to read the second part of this interview.

***

The title of your new book will be Healing the Heart of Democracy, and one of the concepts you’re working with is “the politics of the brokenhearted.” Why are you approaching politics from the perspective of the heart, broken or otherwise?

He saw that this deep “pre-political” layer of our lives is ultimately where democracy will thrive or die.

I’ve long been fascinated with the French intellectual Alexis de Tocqueville who traveled around America in the 1830’s then went home to write what is, arguably, still the best book ever written on American democracy, Democracy in America. In that book he argues that democracy’s future depends in part on the “habits of the heart” that American citizens develop. As early as 1835 he saw that this deep “pre-political” layer of our lives—the level of the human heart—is going to make a huge difference, because that’s ultimately where democracy will thrive or die. I should note that Tocqueville and I use the word “heart” in the same way, to point to that core place in the human self where all of our faculties converge—not only the emotions but intellect and will, intuition and memory, and so forth. The heart isn’t only about our feelings—it’s about who we are as whole persons.

In some ways, with the words “heart” and “pre-political,” you seem to be referring to matters that precede what we typically think of as political activity. Aren’t you talking about social bonds and social practices necessary to becoming well-formed citizens of a democracy?

Politics is about what happens in local life—in families, neighborhoods, and churches.

Yes, that’s right. I believe that the pre-political and the political can’t be separated. You can’t have politics—at least politics in a democracy—without addressing the human heart. Politics isn’t merely about what happens on Capitol Hill or in the White House. “More fundamentally politics is about what happens in local life—in our pre-political lives in families, neighborhoods, voluntary associations, schools, and churches. The question for me is, what can we be doing in these places to develop and put into practice the habits of the heart necessary to activate the kind of citizenship that makes democracy thrive? My question, in a way, is: “Where have ‘We the People’ gone, and how can we get us back?”

Let me tell a quick story that illustrates what I’m talking about. I grew up in suburban Chicago and started down a pretty typical white male, individualist track. I went to an elite college, completed a Ph.D. in sociology at Berkeley, then worked for five years as a community organizer. I cared about community, but had never been immersed in one. So I started visiting various intentional communities with my family, hoping to find one where we might spend a year or so. We ended up at Pendle Hill, the Quaker community near Philadelphia, but one of the places we visited was Koinonia Partners in Americus, Georgia, the birthplace of Habitat for Humanity.

One Sunday when we were there a friend took me to an independent black church out in the country. We went early so we could attend the adult Sunday school. It was a tiny church whose members were essentially sharecroppers—African Americans who had come from a long line of people who had suffered from racism and who were living in real poverty. There were only three members in Sunday school that day. I don’t remember the biblical topic they were discussing, but I’ll never forget the way they were running the class. They were running it by Robert’s Rules of Order. One of the members was the chairperson, the second was the recording clerk, and the third was the sergeant at arms—in case either of the other two got out of line, as I supposed. I was utterly baffled. After the church service, my friend and I had a chance to talk with the pastor. I told him I just didn’t understand it: “Why on earth would a Sunday school class of three be run according to Robert’s Rules of Order? Why couldn’t they just talk to each other?”

He wanted his parishioners to have the skills—I would say the habits of the heart—necessary to participating in a meeting with people unlike themselves.

“Well,” he said, “if you don’t understand that, there’s a lot you don’t understand,” which really got my attention! He said that the members of his church had only recently been able to climb over immense hurdles to claim full citizenship in this society. What he wanted now was for his congregation to move out into the world of American politics—and in order for them to do that, they had to understand how business is done in those settings. He wanted his parishioners to be able to walk into a hearing or a formal proceeding of any sort and to have the skills—I would say the habits of the heart—necessary to participating in a meeting with people unlike themselves, who would likely be using rules that weren’t a normal part of the black church’s habits and practices.

“The members of this congregation are already wonderful citizens,” he said. “They take care of each other in community. They welcome strangers. Look how we welcomed you. You can’t have politics without addressing the political heart. What we need to do now as a church is help all our members gain experience and develop skills that allow them to claim a voice in the larger society.” Well, that left a huge impression on me.

Why do you use the phrase “the politics of the brokenhearted”?

I think that there are a lot of broken hearts these days, broken on the left and on the right over the conditions of modern life. I think “the politics of rage” is really about heartbreak, and that if we could explore what breaks our hearts, we might find common ground. There are at least two ways for the heart to break. There’s the heart that’s been shattered, usually by some external event, and we’re left to pick up the pieces on the way to recovery. But there’s another way to think of a broken heart, as suggested by the words of a Sufi master, Hazrat Inayat Kahn, who said, “God breaks the heart again and again and again until it stays open.” In Christian tradition we talk about the way a “hardened heart” is broken open so that new life can enter in, so that the heart’s capacity can be increased—its capacity for joy, for real sorrow, for compassion.

Their heartbreak led to a largeness of heart rather than to an explosion.

Back to that small congregation in Americus, Georgia, for a moment. Here was a small group of people who were brokenhearted by a long history of oppression and cruelty in a country dedicated to the notion that all men are created equal. But instead of letting that history shatter their hearts into a million shards, they had opened their hearts to a desire to participate as creative members of a larger community. Their heartbreak led to a largeness of heart rather than to an explosion. We all need to practice those “habits of the heart” that allow us to break open to greater capacity and compassion rather than explode in attitudinal, verbal or physical violence.

Now that we have cable stations that cater to every political niche, and continually confirm us in our views, isn’t it getting harder in the political realm for hearts to be broken open in a positive sense?

There is a lot in the human heart that desires totalitarianism.

To be sure. The human heart does not, as some people have claimed, possess an unyielding desire for democracy. There is a lot in the human heart that desires totalitarianism. There’s a part of us that wants a “strong man” to take over and resolve the tensions that beset us, a fascist shadow inside us that wants to blame “them”—Jews or the blacks or young people—somebody, anybody—for all of its problems. That desire of the human heart can lead us down the path of evil. But I side with the writer Terry Tempest Williams, who suggests that “the heart is the first home of democracy” in the sense that the heart is where we wrestle out all of democracy’s key questions, such as (in her words): “Can we be equitable? Can we be generous? Can we listen with our whole beings, not just our minds, and offer our attention rather than our opinions? And do we have enough resolve in our hearts to act courageously, relentlessly, without giving up—ever—trusting our fellow citizens to join with us in our determined pursuit of a living democracy?”

But, it’s precisely trust that seems to elude us. There’s a lot of money to be made, and political gain to be had, from encouraging distrust and enmity.

When we go to the underlying condition we discover what we have in common—even among people who distrust one another.

Absolutely. Media personalities get rich and famous by sowing the seeds of distrust, and politicians manipulate the relationship between trust and fear. The two go hand-in-hand. There’s no denying that American politics are suffused with fear-based politics and the politics of rage. I argue, though, that to treat these problems properly everything depends on the right diagnosis. If it’s really rage that we’re talking about then that diagnosis leads to one kind of treatment. But I believe that behind the rage and behind the fear is a lot of brokenheartedness that we don’t talk about. When we go beneath to symptoms to the underlying condition we discover a lot about what we have in common—even among people who distrust one another.

The question is, How do we get at the underlying conditions? How do we overcome the immense barriers of distrust, pain, and rage? I’m committed to the power of telling stories, and I know that the Collegeville Institute has long shared that commitment as a way to build bridges across faith traditions.

This is part one of a two-part interview with Parker J. Palmer. Click here to read part two of the interview.

Like this post? Subscribe to have new posts sent to you by email the same day they are posted.

Leave a Reply