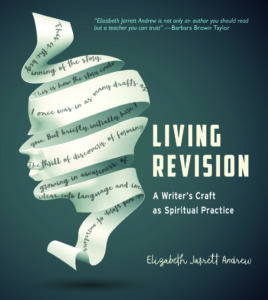

Elizabeth Jarrett Andrew’s latest book, Living Revision: A Writer’s Craft as Spiritual Practice, delves into the way rewriting can also be deeply spiritual. In the following essay, she explores one component of revision: that of privacy, audience, and how the blank page must become a monastic cell.

Elizabeth Jarrett Andrew’s latest book, Living Revision: A Writer’s Craft as Spiritual Practice, delves into the way rewriting can also be deeply spiritual. In the following essay, she explores one component of revision: that of privacy, audience, and how the blank page must become a monastic cell.

When monks approached the fourth-century desert monastic Abba Moses and asked him what they needed in order to know God, Moses answered, “Go to your cell and your cell will teach you everything.” How can we learn to write? Go to the page; the page will teach you everything. And if you also seek to know God through your writing, the page must become your cell.

Moses was inviting his students into the contemplative life—solitude, silence, and practice as the way to know, or bring their full selves to, God. If writing is to become a contemplative practice—that is, our means of making ourselves available for God’s movement in the world—it needs deep privacy. By this I don’t mean a “room of one’s own,” although a quiet, private place is important. I mean internal freedom. I mean sanctuary.

Most writers are all too familiar with the sense of an audience looming over our shoulders. Who cares? Maybe this will be a great American novel! What will my mother think? Consciously or unconsciously, we imagine an audience and play to it. But “if the soul is thinking audience, audience, audience,” Carol Bly writes, “it cannot at the same time be inquiring of itself, kindly but firmly, ‘What are we doing here?’” The ambient noise of self-consciousness interferes with our ability to consent to emergent life, in our hearts and on the page.

For writing to become a means of spiritual growth, we must welcome mystery from the very start.

The cell of the page is a space without audience, what I like to call (with a nod to the anonymous 14th century monk) a Cloud of Privacy and Unknowing. “Privacy” because we need to be alone with the Alone; “unknowing” because we need to intentionally look through what we know toward what we don’t. “No surprise for the writer,” Robert Frost warns, “no surprise for the reader.” For writing to become a means of spiritual growth, we must welcome mystery from the very start.

So you get an idea and it excites you; you bring it to the blank page; you ride your inspiration into a draft. Because audience has been banished there, you then surrender your agenda to the seeds of surprise scattered between the lines. Then you step back and listen. You cultivate that surprise, willfully, as best you’re able. This call-and-response between the writer’s will and the story’s will is the central exchange of writing. The writer brings herself fully forward, whole-heartedly, passionately, willfully, and then releases all that in service of the story. “To be a writer,” Sarah Porter says, “means, perhaps, exactly this: surrendering the defined, expressible self to the wider possibilities of the page.” Surrender—that old, massively misunderstood Christian gesture that is the mystic’s habit. We surrender to possibility. We surrender to unimaginable love.

The peculiar thing about contemplative prayer, as Thomas Merton’s life so graphically illustrated, is that it launches us fully into the world. –The private call-and-response between story and self opens to and is tempered by real human readers. Stephen King put it this way: “Write with the door closed; rewrite with the door open.” I prefer the slower, gentler, “rewrite while gradually, intentionally opening the door.” Here’s how I map out the process:

Literary craft can be a sacred form of hospitality, but only if we’ve first been hospitable to the Spirit in our hearts and drafts. Just as Christians are converted again and again, the hard layers of our hearts gradually peeling away, revision allows writers to reimagine their work again and again, moving it through a transformative process that begins in solitude and ends in community. What begins in the cell of the page has an unstoppable, transformative force.

Leave a Reply