June 13, 2015 marks the 50th anniversary of Jewish philosopher Martin Buber’s death. In the following essay, Peter Huff recalls his first encounter with Buber’s work.

The location where God has repeatedly stepped into my life is an institution all-too-sadly endangered in our society: the used bookstore. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been born again dangling from a rickety ladder to reach the last volume perched on a towering stack of tomes or prostrate on all fours, keen on rescuing a pearl of great price from a long forgotten half-price bin.

The location where God has repeatedly stepped into my life is an institution all-too-sadly endangered in our society: the used bookstore. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been born again dangling from a rickety ladder to reach the last volume perched on a towering stack of tomes or prostrate on all fours, keen on rescuing a pearl of great price from a long forgotten half-price bin.

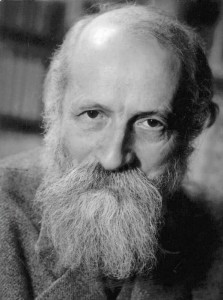

One such bookstore conversion occurred many years ago. I was a brand-new undergraduate and an unwashed novice in the theological guild, just beginning a lifetime of bookshop snooping. One of my earliest discoveries was a deceptively slim volume by the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber: I and Thou. At the time, the author was unknown to me. Nevertheless, something about the title, the author’s name, and the arresting bearded face on the cover made me reach for it. I bought the book, read it, and my life has not been the same since. If I had saved those pennies for a hamburger or the latest Electric Light Orchestra album, today I would not be a professional theologian or a participant in the great adventure called dialogue. In fact, dialogue might not even be a recognizable factor in my operative theological worldview.

“Martin Buber portrait” by The David B. Keidan Collection of Digital Images from the Central Zionist Archives (via Harvard University Library). Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The meeting with Martin Buber, the first non-biblical Jewish writer I ever read, represented nothing less than an invitation into an unexpected new world, a world that called me to confront the limitations of my experience and explore new horizons far beyond my ken. Soon after purchasing the book, I joined the ranks of those young people of the 1970s, who, as Princeton philosopher Walter Kaufmann so colorfully put it, went about clasping I and Thou “to their bosoms.” I even piously carried my paperback copy of the Kaufmann translation on a senior-year trip to Israel. Later, Buber classics such as Moses, Eclipse of God, Tales of the Hasidim, and Two Types of Faith would accompany me to many other sites, sacred and profane.

As a product of the American evangelical subculture, I was unsettled by Buber’s “unwished-for God,” enthralled by what he called the “eternal Thou with many names,” and convicted by his prophetic judgment on religion heedless of the everyday. I was especially intrigued by his attraction to Jesus. Acquainted with little but devotional literature and Billy Graham imitations, I certainly had never seen anything like the following in a work of theological prose: “When a man loves a woman so that her life is present in his own, the You of her eyes allows him to gaze into a ray of the eternal You.” It was all quite tantalizing for a young Southern Baptist. More importantly, Martin Buber served as my initial escort into the realm of living Jewish tradition. No longer would I tolerate the misleading calculus of the Sunday School classroom: Judaism = Christianity – Jesus.

My bookstore epiphanies have taught me many things over the years, including two great postures of prayer: reaching high and bowing low. Half a century after the death of I and Thou’s author, I lift a hand and bend the knee to the Lord of the written word, both new and used and always sacramentally charged. Life, according to I and Thou, is meeting. Thanks be to the eternal Thou, mine was shaped early by an encounter with the bearded Buber.

Like this post? Subscribe to have new posts sent to you by email the same day they are posted.

Some years back I came across an old copy of I and Thou in the library. It looked harmless enough. But it stopped me in my philosophical and theological tracks, so to speak. It was all I could do to refrain from highlighting something on every page. I thought of doing so and then just paying for the damage (perhaps buying it) when I brought it back. I later bought a copy of the Kaufman translation but was somewhat disappointed, perhaps because I’d read him before and knew he was not really open to the God-Thou dimension but also because in the text he dropped the thou and went with you. That seemed to close possibilities down even more. Recently I got a paper back copy of the first English translation by Smith, and I highlighted considerable text and commented away in the wide margins that invited doing so.

I can’t think of any simpler, more direct, more concise prescription for living the good life, being a Mensch, than treating all other persons, all the universe, in an I-Thou rather than an I-It manner, relating to rather than selfishly using and exploiting.