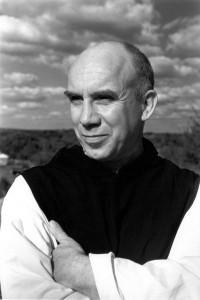

On January 31, 2015, we celebrate the centenary of the birth of Thomas Merton, a Trappist monk and prolific spiritual writer. In remembrance of his birth, former resident scholar Mary Frances Coady shares this reflection on Thomas Merton’s life and work.

At the beginning of his autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain, Thomas Merton introduces himself with these words: “On the last day of January 1915, under the sign of the Water Bearer, in a year of a great war, and down in the shadow of some French mountains on the border of Spain, I came into the world.” This book made him famous—a paradox for someone whose professed desire was to become hidden in God.

At the beginning of his autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain, Thomas Merton introduces himself with these words: “On the last day of January 1915, under the sign of the Water Bearer, in a year of a great war, and down in the shadow of some French mountains on the border of Spain, I came into the world.” This book made him famous—a paradox for someone whose professed desire was to become hidden in God.

He had turned his back on the world and its temptations, and eventually discovered that the world, with all its beauty and flaws, was where he actually lived.

Merton’s life was full of paradox and contradiction. He was an extroverted New Yorker (in the words of his friend Ed Rice, “the noisiest bastard” Rice had ever met) who entered the silent world of the Trappist monastery of Gethsemani in the back woods of Kentucky. In making this choice, he left behind his ambition to become a writer, only to have Gethsemani’s abbot sit him down at a typewriter. He had turned his back on the world and its temptations, and eventually discovered that the world, with all its beauty and flaws, was where he actually lived. Deeply attracted to women and not above using them, he forsook female companionship in becoming a monk, only to fall in love with a young woman when he was fifty-one—and then reaffirmed that the vowed celibate life was the right path for him. He sought solitude in a hermitage even as his gaze turned outward toward society’s evils: war, violence, injustice. Profoundly Christian, he discovered toward the end of his life the spiritual riches of Eastern religions.

The Seven Storey Mountain was published in 1948 and became an immediate best seller. Merton was 33 years old, and had been at Gethsemani for seven years. He knew that fame was illusory and he carried it lightly (referring to the book as “The Seven Storey Molehill” in one letter), but ruefully admitted in his journal that he imagined the popular movie actor Gary Cooper as the star of the autobiography’s film version.

The book covered his peripatetic childhood and adolescence: his mother’s early death and the subsequent shunting of him and his younger brother back and forth from France to New York and points beyond, as his restless artist father struggled to make a living. At school in England, he became an orphan at the age of fifteen when his father died of cancer. The final phase of his youth ended in disaster at the completion of his first year at Cambridge University. (The exact circumstances have never been explained, but bits of information strung together suggest a paternity suit.) Rootless and insecure, Merton landed in New York and enrolled at Columbia University. This was the beginning of a six-year odyssey that would lead him to Catholicism and Gethsemani Abbey.

In the last decade of his life he distanced himself from the author of his best-selling autobiography, explaining that it had been written when he was still in the first flush of conversion.

Post-Mountain, Merton lived for only twenty more years. He died in Bangkok, at a meeting of monastic superiors when he was 53 years old. It was December 10, 1968, the twenty-seventh anniversary of his arrival at Gethsemani. In the last decade of his life he distanced himself from the author of his best-selling autobiography, explaining that it had been written when he was still in the first flush of conversion. Indeed, it has the ring of youthful judgementalism, and he is equally hard on his pre-conversion self and the heathen beyond Catholicism’s gates (he even castigates himself as a six-year-old for not praying when he learns of his mother’s death).

His output over that twenty-year period is remarkable—he wrote dozens of books and articles. In the decades after his death, readers have been treated to the treasure trove found in his journals and letters. Among the most endearing of Merton’s legacies are the tape recordings of his talks to the younger monks. The tapes cover a wide range of subjects: monastic life, poetry, medieval and non-Christian mysticism, early Church teaching—whatever seemed to flow from his own prayer life and intellectual curiosity. He is not an orator. His voice is full of verbal tics (“see?” he says every few minutes, like a tough guy in a 1930s movie), bursts of laughter, and hints of impatience when he asks a question, doesn’t receive the answer he is looking for, and finally answers the question himself. In spite of the austere setting of the talks—it is a Trappist monastery, after all—Merton makes them sound as if he could be sitting in front of a fireplace with a beer (a beverage he was particularly fond of).

The question is sometimes asked: did Merton publish too much? Was the literary quality of his work sacrificed to quantity? Some critics think so. Some others dismiss him because of what they perceive to be unmonklike behavior (the beer, the critiques of the nuclear program and racial inequality, the falling in love). But for those who take Merton seriously, each one has a favorite piece of writing, dog-eared, sentences underlined. Most can acknowledge as their own the searing honesty of the famous prayer that has been repeated in milieus as different as intentional communities, battle grounds, and prisons. From his 1956 book Thoughts in Solitude, the prayer begins, “My Lord God, I have no idea where I am going.” It ends, “I will not fear, for you are ever with me, and you will never leave me to face my perils alone.”

Like this post? Subscribe to have new posts sent to you by email the same day they are posted.

Mary,

I found your comments about Merton, on the occasion of his 100th birthday, thought provoking. Your reference to the first sentence of SSM led me to smile since it is one my favorite opening lines. Thank you. Like yourself I am a graduate of the Ecumenical institute (spring 2000). In fact, during my sabbatical semester in Collegeville I wrote a book (Psychology and American Catholicism) in which I include a section describing Merton’s days in Collegeville.

Hope that your days at The Institute was a formative and grace-filled as my own.