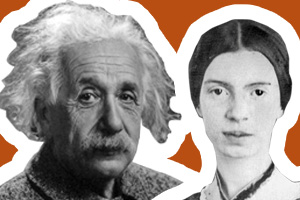

Who’s a more likely model for anyone who wants to write theology: scientist Steven Hawking or poet Annie Dillard? If you’ve read a lot of theology the choice seems obvious, and it’s not Annie Dillard.

Science or poetry?

Albert Einstein and Emily Dickinson

The question leads me to another one. What kind of writing is theological writing? I have asked myself that question often over the years while teaching pastoral theology, theology of ministry, and constructive theology. I still ask the question every time I write a sermon.

Defining the subject matter of theology is easy: Theology reflects on words—spoken or written—about God. But understanding the literary genre of theology seems hopelessly complicated, since there are so many different kinds of words about God, from whispered words of a person’s prayer to voluminous tomes of systematic theology. They are all fair game for theology; they’re all words about God. But do I write about a person’s prayer in the same way that I write about a trained theologian’s thoughts about conversion? And is a systematic exposition about conversion a better way to write about the subject than a story about a persecutor of the church falling on the ground, blinded? But, okay, theology isn’t the same thing as story.

Gradually I concluded that good theological writing requires the form of a poetical essay—a subcategory of what has been called belle lettres, or fine writing. At first I thought that the word essay could carry all the freight. A good essay is an attempt to find meaning. It draws the reader into the essayist’s topic, and by its carefully crafted sentences and paragraphs, it engages the reader in a mutual exploration of that topic.

But something was still missing: an emotional quality, a passion that may not always appear in essays. The adjective poetical was needed to complete my definition. Good poetry is radically honest, confessional, baring the poet’s soul however readers might receive that disclosure. Good poetry finds the best words and images to express a poem’s content, particularly its emotional meanings. Good poetry pays attention to rhythm, cadence, flow, melody—all those musical qualities that are at the heart of poetry. The best theological writing should combine the craft of an essay with the passion and music of poetry.

Why does so much theological writing seem woefully devoid of the qualities of a good poetical essay? It may simply be that many theological writers pay little attention to genre, and write as they have been unconsciously tutored by the examples of their professors at seminaries or divinity schools. Those examples tend to have a common source in the analytic term paper. It may also be that reading and analyzing classical theological texts instills the values of logical entailment and scholarly caution that impede writing in the style of a poetical essay. If a writer is hyper-aware about possible objections to something said, the writing suffers, dying the death of small claims and defensive qualifications. And if the norm of a comprehensive coverage of all possible theological topics has taken root in a writer’s mind, following the examples of great systematicians like Aquinas, Calvin, Barth or Tillich, who would risk addressing only one topic without at least the underlying plan to move on to more topics, or the whole list? The essay of poetic exploration gives way, yielding to the system.

As a teacher of theology and an advocate for the essential role of theology in enlivening the church, I have slowly come to realize that the best examples of theological poetical essays are to be found in sermons and devotional writings, not in writing usually associated with systematic theology. A good sermon wrestles with profound theological questions, but with the language and images of a poetical essay, not scholarly discourse. A good sermon is confessional, not argumentative. A good sermon invites the hearer to consider (or reconsider) following Jesus Christ; it does not try to compel that assent by the weight of evidence.

A good piece of devotional writing invites the reader into a place of meditation and prayer, not a classroom. Difficult theological questions are not absent, but are treated as poetic explorations of words and images shared in a community of prayer, where the aim is communication, indeed communion, not definitional clarity.

I am not saying that all sermons or every piece of devotional writing are good poetical essays. Most of them, including my own, are not. But preachers and devotional writers (and theologians!) would do well to pay more attention to the canons of a poetical essay as they write. If that were to happen, I believe, the taste for theology would come alive for both church communities and individuals.

Images: Einstein and Dickinson, available through Wikimedia Commons.

Like this post? Subscribe to have new posts sent to you by email the same day they are posted.

An amazing post with great tips as always. Anyone will find your post useful. Keep up the good work.