At age 35, Kate Bowler was diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer and given less than a year to live. Two and a half years later she continues to live with her terminal illness, balancing the roles of assistant professor at Duke Divinity School, wife, and mother to a toddler. Following a popular essay on death and the prosperity gospel published in The New York Times in 2016, Bowler embarked on a book-length memoir to dig into the “truest, hardest things” about living with cancer.

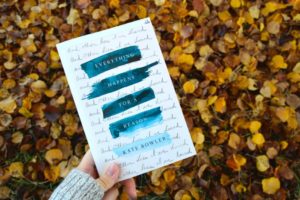

Her resulting book, Everything Happens for a Reason, and Other Lies I Have Loved, explores the meaning of her illness in terms of the prosperity gospel she studies as a religious scholar, and in terms of the liturgical calendar and what it teaches us about the role of the Church in times of suffering. She wrote the bulk of the project at the Collegeville Institute during the 2016 summer workshop with Lauren Winner, Christian Spirituality and the Writing Life.

Our editorial associate, Susan Sink, who is currently in remission with stage IV ovarian cancer, had a conversation with Bowler about her book, which releases tomorrow. While remaining clear-eyed about her prognosis, Bowler has written deeply about what it means to hope without the promise of a long life ahead.

Kate Bowler

Hi Kate, thanks for talking with me today. Before we talk about some of the issues in your book, I have to ask, how is your health right now?

We are in the “managing illness” phase and out of the “apocalyptic crisis” phase. I’m still receiving treatment. I don’t like to get too specific about my health and treatment, because it just becomes absurd really quickly. Once you’ve abandoned a world of certainty, the future is a fuzzy thing. I just try to make as much room in the present for my life as possible.

The first thing I want ask is about the experience of writing through treatment. I wrote about my cancer treatment, too, but at a certain point, I stopped trusting what I was writing. People reading my blog let me know that my writing resonated with them, but I sometimes wondered if they were responding more to the sense of how in-the-moment this writing and reflection was, even more than what I was writing.

Writing first the article that appeared in The New York Times after my initial diagnosis and then the book, was such an immediate and urgent thing. I’m so grateful that it reaches outside my own experience and means something to readers, but at the time I treated the writing more like an archeological experience—I was just going to dig until I found the truest, hardest thing, and then I was just going to stay there until I learned something.

In the end, I hope the book will resonate with others who also feel like pain made them a loser. I was exhausted by how pathetic being sick made me feel. And that surprises me because my own personal theology has such generosity toward other people who are suffering. But it was such a different thing to go through that myself. It made me hope that in whatever I write, that readers will always feel like they are people to be loved, not problems to be solved.

That was so much of my experience: feeling like a problem to be solved. People would ask me: Did your parents have this? Were you overweight? Were you eating this or that bad thing? Did you use your cell phone for too long? They all seemed to think that I must have done something, that there must have been a hidden thing that I did that caused a 35-year-old to get stage IV colon cancer. It became such a burden to feel like a problem. It’s almost like a reflex. People think, “If I can find a way to explain why you have terminal cancer then I don’t have to feel like this is going to happen to me.”

I see that as blaming, not really trying to solve a problem. In some churches, this fear feeds into categorizing people as insiders or outsiders. If I can make you other, because you are sick, then I can’t really be expected to understand where you are—and in the process you become outside. It can be patronizing.

The prosperity gospel is a rarified version of this; it does create an inner circle of righteous and an outer circle of people who they think of as sort of average Christians. Those average Christians have a check signed by God for them but they just don’t take it to the bank. There’s a lack of effort or they’re just not bridging the gap. Somehow the “righteous” managed to claim God’s blessings, but the other people didn’t.

You are a scholar who wrote the first-ever history of the prosperity gospel. Did the prosperity gospel offer you positives you could apply to your current situation?

My time with the prosperity gospel taught me a lot of things about how basic our desires are. What we all want from God is so much more ordinary than I expected. You know, bodies that work most of the time, enough money to do something fun sometimes, and family members that don’t want to murder us — it’s all such basic stuff. Watching this pageantry of desire on display in the churches I visited really reinforced to me that their needs were quite ordinary and my needs were quite ordinary as well.

On the inspirational front, it also taught me about expectation and hope. People who subscribe to the prosperity gospel have such a playfulness about what they imagine God might do. That was inspiring for me. Maybe I should pray for—I have never been a person who would pray for a close parking spot—but maybe I should imagine God more in my daily life than I have before. I tried to keep that spiritual sense of expectation. I would see people laboring over prayer for their mortgages or a better teacher for their kid’s next year in school. It was a reminder that expectation can create better faith. When I had to face my own limitations, that was a big shock for me. I don’t know what I expected, but I expected more than this. I really did.

Of course you did. That was a more than reasonable expectation at 35.

Coming face to face with my limitations, I realized the language of endless possibilities in the prosperity gospel is really pernicious in many ways. In the end, it’s just not true.

In your book, you write about a sense of peace that you experienced. I resonate with that in my own cancer journey. Everyone told me that isolation and loneliness would be the hardest part of having cancer. I’m an introvert and you seem like an extrovert, but I didn’t feel lonely, ever.

I’m less of an extrovert than I used to be. I’m curious, how long did you have that feeling? Was it when you were really sick that you felt an infusion of God’s presence?

I had 18 weeks of something called “dose dense” chemotherapy, then surgery. I had the frustration over my limitations, which was the hardest part, not being able to do what I used to do. But I also really felt the presence of the Holy Spirit the whole time. Just a quiet, peaceful presence. What was that peace like for you?

It was another surprise, to be flooded with a sense of God’s presence. And it made me curious about whether, when we come to the end of ourselves, God fills the gaps, just by being there. I thought I would feel so much emptier than I did.

You can hold onto that experience always. It doesn’t last necessarily, but you can know it to be true.

How long did you feel that?

I felt it the whole time I was in treatment. Until the end of treatment. For me, the anxiety really started after we ended treatment and then I had to figure out what to do next. In your book, you write about having a clear scan and feeling like that granted you another 30 days because you qualified for more treatment. The oncologist describes the stage I’m in now, remission, as “watchful waiting,” and as long as the antigen is low, I get three more months. It raises all these questions: What should I be doing? Should I spend all my money and travel? Should I put in the garden?

These are real questions.

And that comes down to living in the present, and also hope. You do have to live into even just a little future. You have to ask, how much future should I give myself?

Yes, that’s right. That’s a great way of putting it.

You’re teaching, so you have to sign up for another semester.

Yes, and everyone’s always trying to get me to make plans. It’s exhausting. In academia, too, you’re asked to book sometimes a year in advance for things. And I have to say, “Well, that sounds really nice, but…” For lots of people it’s very difficult to figure out how far out to make plans. Other people I’ve met along the way say, like you, that the hardest thing is to figure out how much future you can imagine for yourself. It always bugs me when old people talk about retirement—I want to say screw you, you know, you’re fine. Just get on with it. Most people imagine an unlimited future. And it is a delusion, of course.

I was just reading an article about a little kid who finished her chemo and on the one year anniversary she was killed in a car accident. I find those are the gut-punch articles for me. We create story arcs in our mind. If people do something hard, then we imagine the arrow always goes up from then on. It’s hard enough to imagine fighting the cancer; nothing horrible can happen after that. It’s hard to imagine a future you can’t possibly control. I think you’re right, you just imagine little bits at a time.

Your book ends with this sentence: “I’m going to die—but not today.” For me, I found myself coming down on the side of saying: “I’m going to live until I die.” It sounds obvious.

It’s not. It’s so not obvious to most people. And I imagine most people live like they’re lightly sleeping. And so, sometimes, that does sort of feel like the gift of having cancer — learning to stay awake.

And also, you have to be okay with what that life is going to look like. I’m sure that’s a huge struggle for you, especially raising a child.

Kids have a language of unlimited future. You look at them and all you see is the future. That’s what is so beautiful about them. The laws of potential. It’s one of the most gorgeous things you can watch in slow motion. I think that’s the human experiment—how do you live until you die? That’s the hardest part.

Another related issue is hope. Hope is important, even for those who are being absolutely clear-eyed about what is going to happen. What does hope look like to you?

I don’t know. I have a greater sense of what it’s not. It’s not an expression of unlimited potentiality. I notice that people often have a hungry feeling when they imagine they can have anything forever. Hope is more like love, like an expression of profound joy in the possibilities of my friends to create new ways of being alive, and my own ability to be with them every day as much as I can. I think of hope more like a space within limits, confined rather than unlimited space.

I try hard to pay attention. For me hope, part of it, is living beautifully right now. I used to notice this with academic conferences—there would be a dozen receptions in a row, and people would go from reception to reception as if they are still hungry, and thinking there is probably someone better to hang out with at the next one. Early on, I wished I had an app where a little alarm would go off to tell me when I’d reached peak fun so I could recognize it and experience it and stop that hunger for something better.

I decided I was going to pay attention to the moment of peak joy in my day. And it might be at 8 a.m. Like the other day I was holding my son and he was wearing a dragon costume and we were dancing to a song about dragons and I realized: “This is the best part of my day. And if I don’t slow that moment down and pay attention, I will not be living fully with the people I hope to care about best.”

That’s amazing. That is living in the present.

You organized most of your book around liturgical seasons. One thing I love about liturgical seasons is that they’re circular, not linear. How did using this form help you organize your thoughts and experiences?

I didn’t think much about seasons until I had limited seasons. And then the looped quality of the liturgical calendar made me think maybe we’re just supposed to be learning the same lessons over and over again, as prone as we are to forgetting. My favorite now is Lent. I am all about Lent. I’m thrilled the book will come out right before Lent. It is really the season of “take courage,” and the church is supposed to stand with us and take down the darkness.

And if the church can’t do that, and it Easters the crap out of my Lent, then the church has failed. It has missed a fundamental lesson about being human. It has missed the dark side of the incarnation. You have to let tragedy and finitude take up space—take up space in the church and in your friends’ lives—and you have to sit there. And you have to look at tragedy and finitude whether you like it or not. Then we learn to be hopeful again at Easter. And then we cycle to waiting in darkness again for the in-breaking of the kingdom, all over again. And again.

But my very favorite season in the cycle is Lent.

And that was not true before cancer?

No, not really. But, like you, I had a lot of experience in Catholic Churches. I went to Catholic school and always thought: “Wow, these people are amazing about being sad. There is something to learn about that. They can teach me.”.

How do you feel about doing publicity for the book?

Oh, it’s so funny. It’s so funny. I wrote it so privately. Now to become a public person? I don’t know how to feel about it.

I learned a lot the first time around because when I wrote the first New York Times essay. I was so dumb, really. I forgot, of course, that it would go out to the public. I wrote it because I thought it was true. Then you learn, of course, that the whole world is full of brokenness and that people will react to you in different ways than you anticipated, if you even anticipated anything. People are exhausted and they’re just clawing for a hopeful something. They need an entry point into other people’s humanity to help them deal with their own, and they need an opportunity to express themselves, and sometimes that means writing emails to a stranger on the internet.

Is there anything else you want to tell me?

I just have to say that I adore the Collegeville Institute. It is a beautiful space and a gift to the community. The hospitality I received there was a big part of being able to write this book.

Thank you, Kate, for your book and for your life. For being public and sharing your experience. It really does help everyone to face uncertain futures. I hope for you many days of dancing with dragons.

Thank you for reading the book with such generosity. I’m so glad for your remission. I’m impressed that you press on with such fortitude. Staying creative and open after something has knocked you off at the knees is hard.

Like this post? Subscribe to have new posts sent to you by email the same day they are posted.

Leave a Reply