This essay is a product of the Collegeville Institute’s Emerging Writers Mentorship Program, a 13-month program for writers who address matters of faith in their work. Each participant has the opportunity to publish their work at Bearings Online. Click here to read other essays from the 2021-22 Emerging Writers Program cohort.

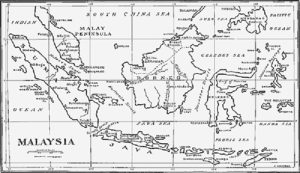

I don’t know her name, but I have been looking for her in my free time. Usually while I’m chewing on my dinner, I take one of the three books stacked on my coffee table and flip through them. These books contain five decades of compiled reports in Mandarin and English from the Methodist church in Borneo, Malaysia. I thumb through first-person entries written by missionaries for a Methodist magazine, usually detailing updates from Chinese Methodist schools. I am ignoring any names that don’t sound like a woman’s. I’m looking for someone who fits this missionary profile—female, single, American, Methodist—from the early 1900s. According to my grandmother, it is because of this missionary that her family escaped the poverty of China, migrated to Malaysia, and converted to Christianity. My grandmother credits her for “saving” our family both spiritually and physically.

I don’t know her name, but I have been looking for her in my free time. Usually while I’m chewing on my dinner, I take one of the three books stacked on my coffee table and flip through them. These books contain five decades of compiled reports in Mandarin and English from the Methodist church in Borneo, Malaysia. I thumb through first-person entries written by missionaries for a Methodist magazine, usually detailing updates from Chinese Methodist schools. I am ignoring any names that don’t sound like a woman’s. I’m looking for someone who fits this missionary profile—female, single, American, Methodist—from the early 1900s. According to my grandmother, it is because of this missionary that her family escaped the poverty of China, migrated to Malaysia, and converted to Christianity. My grandmother credits her for “saving” our family both spiritually and physically.

I don’t doubt my grandmother’s account, but I can’t bring myself to jump to a full adulation of this Methodist woman missionary. I often wonder if my parents would have less of a racial inferiority complex, feeling “less-than” white people, if it weren’t for Christianity. Many of the songs we sang in church and theology books we read came from Europe, Australia, or North America. It was hard to shake the feeling that majority “white countries” were ahead in all respects—economically, intellectually, and religiously. What would we be like if we never met that missionary? Would we be better off, or not? If I could time travel and meet her, I don’t know if I would feel angry or grateful, or both.

I wonder if my parents would have less of a racial inferiority complex, feeling “less-than” white people, if not for Christianity.

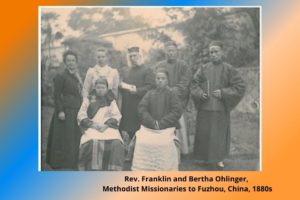

My family is far from unique in owing our Christian faith to the work of missionaries. Today, two-thirds of Christians live in the “Global South,” meaning Africa, Asia, and Latin America. That means that there are now more Christians in countries that missionaries evangelized than the countries where they came from. These countries all, not coincidentally, suffered from imperialism. My Chinese ancestors’ faith, for instance, was made possible by British cannonballs. A series of humiliating military defeats at the hands of the Queen’s Empire forced China to legalize the import of opium, permit missionary activity, and open to foreign trade. Fuzhou, the southern port city of my ancestors, was one of five Chinese ports opened to foreigners under the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842.

I don’t know the name of the missionary who helped my family, but I’ve started to gather context clues. By 1890, 60 percent of all missionaries in China were women. According to theologian Kwok Pui-lan, the mission field tended to attract ambitious and idealistic young women from the rural Midwest, many of whom chafed against Victorian norms of female domesticity. “In central Ohio, an ambitious woman might be an old maid schoolteacher or a preacher’s wife; in China she could stand out as an idealistic reformer, perhaps even be allowed to preach in church pulpits on home visits,” a researcher, Molly Frost, wrote for Methodist History.

These women missionaries walked into a cultural context where girls’ feet were bound to win a desirable husband and where female infanticide was often practiced by poor families. That was the milieu into which my great-grandmother was born in Fuzhou. She was the third daughter—no son yet—born to the great disappointment of her mother’s mother-in-law who was incensed and, despite protests of the mother, threw the baby girl out into the fields to die.

At the time, her father did not know that his wife had given birth and was out working in the fields. He heard the screams of a baby and rushed towards her, finding her lying under a tree. Thinking to himself that since his wife was about to give birth she might be able to nurse her, he brought the baby to his wife only to realize that this was his child after all. They managed to keep her and raise her against the wishes of the mother-in-law. When my great-grandmother was roughly ten years old, her father died. The mother-in-law promptly evicted the entire son-less family—my great-grandmother, her sisters, and her mother. They took refuge in an abandoned Buddhist temple in the cold of winter. As my grandma tells it, a young American woman missionary found them there. She offered to bring them with her on board a ship to what is now known as Malaysia, where she was headed to continue her evangelism amid the sizable Chinese Methodist community there. Since they had a few relatives in that country, my family agreed. Several seasick months later, all five women landed in the place where my grandmother, father, and eventually I would be born.

The young American missionary offered to bring them with her on board a ship to what is now known as Malaysia.

My grandmother doesn’t remember – and frankly may never have known – the name of the missionary, when she left China, or where in America she was from. All she can recall from meeting her as a child is that she was likely in her fifties, and was very loving, letting her and other kids touch her brown hair. My grandmother, like most everyone else, only called her by her title, “师姑 (Si Gu),” which literally translates to Teacher Auntie. “We all became Methodist because of 师姑, we loved her. She didn’t have money to buy us things to eat, she was very poor, but she loved us all equally. Without her, we would’ve been poor or dead in China,” she said. In other words, if it weren’t for Si Gu, maybe I wouldn’t exist today.

While researching this story, I came across the article by Frost in Methodist History. In it she describes a photo, located in one of the papers of missionaries in Fuzhou, of a “baby tower for female infanticide” in north China. It was a small hexagonal building with a door and a tiny window on the upper level. Frost writes, “It is not clear whether this was a place to leave unwanted, living children, a tomb for the tiny corpses, or a memorial structure.” It clicked then for me how common female infanticide was in China at the time. What was the point of raising a daughter if she was going to leave your family and not take care of you? If my great-great-grandmother had told her husband to leave the baby by the tree, it would’ve been an understandable, economically “rational,” decision. Ditch the girl, save the family.

The turning point in my family’s story, then, was not when the missionary appeared at the temple. It was when my great-great-grandmother chose to keep her daughter—my great-grandmother—at great sacrifice to herself. She did so knowing this would place her in immense conflict with her mother-in-law, who ruled the home. And even after she was expelled from that home, she chose to stick with her daughters. They would live or die together.

Christianity did not save us; my great-great-grandmother did.

Christianity did not save us; my great-great-grandmother did. But Christianity did provide her with an alternative structure of beliefs that aligned more closely with her values. And so, she converted—not as an act of passive acquiescence, but as an active choice to leave behind the world she knew, spurred on by love for her daughters. That is the real legacy that she left behind: a willingness to buck the tradition in which she was raised and start over with a tradition that made more space for her daughters and her.

Like this post? Subscribe to have new posts sent to you by email the same day they are posted.

How sad your own hobby horses prevent you from celebrating the glory in your family’s history. How sad you deny the agency of your great-greatgrandfather and the lady missionary. How sad you don’t realise the transforming power of faith in Christ.

A missionary. 🙂