By Jill Kandel*

By Jill Kandel*

Reviewed by Sari Fordham

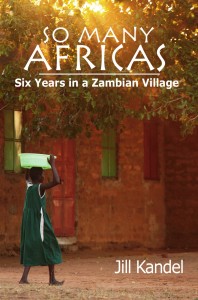

Autumn House Press, 2015, 184 pp.

Winner of the 2014 Autumn House Nonfiction Prize, selected by Dinty W. Moore

A perk of teaching is that students ask me for book recommendations. They hold out questions like plane tickets, hoping to be taken somewhere new and interesting. I love these questions, these book questions, but there is one that left me floundering. “Do you know any good memoirs about marriage? I mean, a marriage in progress.” The student asking was newly engaged and writing essays about soul mates and true love. I wanted to give her something sturdy to consider.

“Sure,” I said, and then stopped. The nonfiction books that rose to mind were about marriages that had ended in death or divorce. Memoirists, it seems, will brave any topic, except one. Spouses might stroll casually through a memoir, but relationships are rarely unpacked, and then, returned intact.

In So Many Africas, however, Jill Kandel writes not only about the landscape of a new country, but also of a new marriage. She and her husband Johan have been married two months when they arrive in Zambia. Jill is from North Dakota; Johan is from the Netherlands. She has spent one summer previously in Zambia (on his request) while he has worked in the country for three years.

Together, they return: certain and uncertain. Johan will work for the Organization of Netherlands Volunteers (ONV) and improve agriculture in and around the village of Kalabo. Jill, whose American nursing degree is not recognized in Zambia, will manage the household. In the first chapter, it is clear whose job is harder, or at least lonelier. While Johan makes decisions that will positively impact their community for years to come, Jill goes to the butcher and purchases a hunk of cow, hide still clinging to it. She wryly contrasts her experience to a U.S. grocery store where the hamburger meat is encased in Saran Wrap.

The writing throughout the first chapter is vivid and humorous, making unexpected leaps and connections, but it is the conclusion that establishes Jill’s narrative ambition, her willingness to be raw. As the chapter closes, Jill shifts to the second person point of view: “I see you, but you have not looked up and seen me.” The you is Johan, and in that moment, she feels invisible. It is a scene that could be self-pitying, but is instead told with tenderness for both herself and her young husband. She proceeds to describe their flaws: she does not show, he does not look. The overarching marital conflict is established, and it is all I can do to not flip to the last chapter and see if Jill and Johan are still married.

While marriage is a thread in the memoir, living in Africa is the dominant braid. Zambia is on the edge of the Kalahari Desert, and in the prologue, Jill references the sand that blows through her life even after she leaves. “Memories covered by sand are not safe,” she writes. When they live in Zambia, her husband must contend with the sand as he thinks about planting crops, her eldest daughter loves how the sand squeaks as she runs across it, and Jill must sweep and sweep like all the women in Kalabo.

Jill visits some of the expected themes of life in Africa—the snakes, the cockroaches, the fellow expats who eat your limited food—but her experiences are uniquely hers and she does not write in generalities. She gives birth twice in Kalabo, attended each time by Dutch doctors who have distinct opinions about Novocain. When she brings her daughter home, she is visited by mothers in the village. “The women that day do not ask me about my career goals. They do not turn their backs unimpressed at my feeble answers or the names of my degrees. They all know what it is to be a woman. And it is enough.”

While Jill might feel ambivalent about living in Zambia, it is clear that she is respectful of her neighbors and that she forms deep bonds. At a funeral for a friend, she holds hands with his Zambian wife all night and admires the way Africans mourn. “Everyone sits generously, without shame,” she writes. Jill could also be describing her own prose style. She tells her story through multiple points of view, using chapters that might be as short as a paragraph or as long as ten pages. These artistic decisions do not feel haphazard; rather, it feels as though Jill is writing as close as she can to the truth.

So Many Africas was selected by Dinty Moore as the winner of the Autumn House Nonfiction Prize. In 32 chapters (plus a prologue and epilogue), Jill examines the history she brings to Zambia, the loneliness she feels, the people she meets, the loss she witnesses, and the state of her marriage. Her honesty makes this book worth reading, and her evocative writing makes it worth recommending to everyone you know.

Now that I am finished, I am left with many moments from Jill’s life, but the image that rises first to the surface is her description of ant day. “Did you ever see a cloud of ants above you in the sky? Did you ever see a hundred hungry birds, mouth open, wings flaring? I did. I saw those dense saturated clouds while I stood next to Mr. Albert. Stood in the African sun, staring up at the world and the open blue sky.”

* Jill Kandel participated in the 2013 summer writing workshop, Believing in Writing: A Week with Michael Dennis Browne.

Like this post? Subscribe to have new posts sent to you by email the same day they are posted.

Leave a Reply