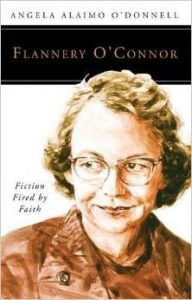

In this interview with Angela Alaimo O’Donnell, writer, poet, and professor at Fordham University in New York City, Elisabeth Kvernen asks about her recent book, Flannery O’Connor: Fiction Fired by Faith. During their conversation, O’Donnell discusses how O’Connor’s writing was influenced by her faith, the role of violence and the grotesque in O’Connor’s stories, and lessons that aspiring writers can take from observing O’Connor’s life.

In your book you share a quote by another O’Connor biographer, Jonathan Rogers—“The story of Flannery O’Connor’s life is the story of her inner life more than her outer life.” What difference does this observation make for your own study of O’Connor?

In your book you share a quote by another O’Connor biographer, Jonathan Rogers—“The story of Flannery O’Connor’s life is the story of her inner life more than her outer life.” What difference does this observation make for your own study of O’Connor?

O’Connor once mistakenly predicted, “As for biographies, there won’t be any biographies of me,” because “lives spent between the house and the chicken yard do not make exciting copy.” A statement like this demonstrates O’Connor’s acute awareness of the circumscribed nature of her life, particularly after she fell ill with lupus and was confined to her mother’s farm for the last 14 years of her life.

O’Connor is right, in that most people are not fascinated by the daily rounds and rituals of rural life, but what she did not foresee is how interested in her imaginative life her future readers would be. It is nothing short of miraculous to read O’Connor’s letters and discover how determined she was to continue correspondence with her friends, fans, and fellow writers. Despite the debilitating disease she suffered from, O’Connor wrote generously and voluminously, as this was her way of carrying on conversation. And we, the readers, have the rare pleasure of eavesdropping on those conversations, overhearing her confide her most private thoughts to those she loved and trusted. So, yes, reading O’Connor’s letters gives us a glimpse into her rich inner life, and the reader can’t help but fall in love with this bright, clever, witty, often prickly young woman. We learn so much about her in the course of the letters that by the time we reach the end, it feels as if we have become part of Flannery’s circle of familiars and that she has been writing to us as much as to the friends named in the salutations. Flannery’s story is such a poignant one—we watch her live and we watch her die—so in reading—or writing—her biography, we are ushered into intimacy and mystery.

In your biography you highlight how O’Connor’s Catholic faith influenced her voice and vision as a writer. Can you introduce us to your insights about the influence of her faith on her writing?

O’Connor was a serious Catholic from childhood through adulthood. Being brought up Catholic in the Protestant South set her apart. She was part of a small-but-mighty community of Catholics—first in the fashionable Irish Catholic Ghetto of Savannah, and later in the circumscribed Catholic world-within-the-world of small-town Milledgeville, Georgia. But they all knew they were different in some fundamental ways from their Protestant neighbors, who were frank about their anti-Catholicism. Being part of an embattled minority makes one sensitive to and protective of one’s origins and traditions. The fact of O’Connor’s Catholicism was foundational to her identity, to who she was and how she viewed the world. This awareness informed all aspects of her life, not least of all her writing.

O’Connor was a serious Catholic from childhood through adulthood. Being brought up Catholic in the Protestant South set her apart. She was part of a small-but-mighty community of Catholics—first in the fashionable Irish Catholic Ghetto of Savannah, and later in the circumscribed Catholic world-within-the-world of small-town Milledgeville, Georgia. But they all knew they were different in some fundamental ways from their Protestant neighbors, who were frank about their anti-Catholicism. Being part of an embattled minority makes one sensitive to and protective of one’s origins and traditions. The fact of O’Connor’s Catholicism was foundational to her identity, to who she was and how she viewed the world. This awareness informed all aspects of her life, not least of all her writing.

In the prayer journal that O’Connor kept while she was a student at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop—a journal that takes the form of letters to God—the young apprentice writer expresses her anxiety about losing her faith in the secular environment she finds herself in and losing sight of the fact that all of her stories come from God. The young O’Connor prays that she might learn how to incorporate her faith into her writing, to write stories that somehow evince the eternal truths she has learned and believed all of her life as a Catholic.

Later in life, when O’Connor is surer of her craft, she explains in one of her essays that the writer writes with the whole personality—all aspects of her vision and beliefs come into play when she creates a story, unconsciously or otherwise. Chief among her faith convictions is her belief in the Fall, the Redemption and the Judgment—and it is no coincidence that this Judeo-Christian narrative constitutes the backbone of every O’Connor story.

In addition, O’Connor’s stories are glaringly Catholic in a number of ways. One of her characteristic themes is the goodness of creation. Her stories are full of characters who believe that “the world is almost rotten” (“The Life You Save May Be Your Own”), and that the present is a pathetic remnant of some glorious past (“A Good Man is Hard to Find”). In O’Connor’s spiritual ethos, these characters are ripe for a conversion, because the Catholic vision does not accommodate such thinking. Even as the family in “A Good Man” rushes past the Georgia landscape on their doomed drive to Florida, not wanting to look at it because it is (supposedly) so ugly, “The trees were full of silver-white sunlight and the meanest of them sparkled.” They are blind to the fact that the world is charged with the grandeur of God (to borrow a line from Gerard Manley Hopkins). In O’Connor’s stories, the divine is immanent in the natural world, and the supernatural has a way of breaking into the lives of ordinary people.

This is not to say that only goodness is evident in the creation. In fact, O’Connor is well aware of the presence of evil. There is a darkness and a bloody-mindedness that pervades the stories, making many of her readers uncomfortable. And yet, those sources of darkness often become conduits of grace in the lives of the characters. Again, God works through nature—grace manifests itself in inconceivable ways—and human beings discover the hard truths of the cross, the challenges of living a faithful life, and the fact that (in O’Connor’s words) “even the mercy of the Lord burns.”

Granted, this is not a warm and fuzzy version of Christianity or Catholicism. But O’Connor is firm in this. As she writes in one of her letters, “What people don’t realize is how much religion costs. They think faith is a big electric blanket, when of course it is the cross.” Living with a fatal degenerative disease, O’Connor knew something of the cross and does not shrink from incorporating its hard lessons into her stories.

Was O’Connor’s integration of her faith and writing a central reason why you decided to write her biography? Were there other aspects of her life that you thought needed attention?

Yes. Much as I admire the accounts of her life written by previous biographers, I felt none of them paid sustained and focused attention to the relationship between her faith and her writing. These are big books, full of marvelous detail about all sorts of aspects of O’Connor’s life, and they are well worth reading; but the narrative of her faith life and its connection to the development of her imagination is either absent or it gets subsumed in the welter of incident and detail.

I wrote this book by invitation from the Liturgical Press. They were developing a series entitled “The People of God,” commissioning brief biographies of consequential Catholics that might serve as introductions to their lives and works. I accepted the invitation because it gave me the opportunity to spread the good news about Flannery O’Connor and her magnificent stories among a readership that might not otherwise know her. As such, I chose to emphasize aspects of her life and to analyze stories that would speak to that readership and demonstrate the ways in which a Catholic writer such as O’Connor is responding to a call, practicing a vocation, as surely as a priest (such as Oscar Romero) or a pope (such as John Paul II), a monk (such as Thomas Merton) or a social reformer (such as Dorothy Day). In a sense, I wrote the book to champion the cause of the Catholic writer as much as to tell O’Connor’s story. As a Catholic writer myself—and an admirer of many other Catholic writers—this is a theme that lies near and dear to my own heart.

In what key ways did O’Connor’s external circumstances shape her career and faith journey?

All of our journeys are shaped in some measure by our external circumstances. As enfleshed, embodied beings, we experience the world incarnationally, through the senses, and we pay close attention to sensory experience, learning what it has to teach us.

This is certainly true of O’Connor, as well. Flannery was shaped by the fact of her Southern-ness and her female-ness, by the fact that she was an only child, by the fact that she lost her beloved father as a teenager and then was raised by a houseful of women, by the fact that she was an outsider at Iowa and then later at Yaddo among secular artists and intellectuals and then later in New York City. In fact, it was her uniqueness among the writers and editors she met that caught peoples’ attention and made them more interested in reading and then publishing her work than they might have been otherwise.

Of course, the single most definitive external circumstance was the fact that O’Connor was diagnosed with lupus at the age of 25, just as her career was being launched. This necessitated her move back to rural Georgia and to living in a kind of exile for the next 14 years until her death at 39. This was a circumstance that was hard for her to bear—yet, despite this hardship, O’Connor confesses that coming back to Georgia was the best thing that could have happened to her. It was there that she discovered and committed herself to her material—the bizarre and complicated lives of her fellow Southerners and the inimitable idiom they speak. O’Connor had an ear for these voices and an eye for their oddities, as well as their humanity, and set about writing stories that were like no one else’s and that would gain her the fame that she has acquired.

Her illness also profoundly affected her faith life. O’Connor knew what it was to suffer every day. She was humbled by her disease, at times, but it also made her patient and taught her to hold the things of this world lightly. People are often amazed when they read O’Connor’s letters and observe her good humor in the face of the disease (and the medication) that was ravaging her body. While it’s true that some of this is bravado, it’s also an indication of O’Connor’s faith and her understanding of the Christian mystery. She understood that tragedy is unfinished comedy. The crucifixion is not the end of the story—the resurrection is. Death is ultimately defeated by life. Suffering and pain are passing circumstance, so why not grin in its face while you bear it?

O’Connor wrote in one of her letters, “I have never been anywhere but sick. In a sense sickness is a place, more instructive than a long trip to Europe, and it’s always a place where nobody can follow. Sickness before death is a very appropriate thing and I think those who don’t have it miss one of God’s mercies.” Ultimately, O’Connor conceived of her illness as a form of grace. What can one say in the face of such faith?

In your book you discuss the role of violence and the grotesque in O’Connor’s stories. Could you explain why she often felt it necessary to introduce violent action and extreme characters in her plots?

O’Connor herself explains her affinity for violence and the grotesque as a mainstay of her fiction. In one of her essays, she states the following: “When you can assume your audience holds the same beliefs you do, you can relax a little and use more normal means of talking to it; when you have to assume it does not, then you have to make your vision apparent by shock—to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost blind you draw large startling figures.” Writing fiction that takes as a foundational ethos religious ideas (the Fall, the Redemption, the Judgment) for a secular audience is a challenge. O’Connor feels the need to shock her readers into an understanding of the high stakes of human choice and human life. What better way of doing this than through violence that shakes readers out of their comfortable (and deluded) relationship with the world, making them feel vulnerable, uncertain, and more likely to consider the ultimate questions that O’Connor believes are at stake every moment of our lives.

O’Connor also explains the presence of violence as a necessary condition for her characters to be shaken out of their complacency, as well. “In my own stories I have found that violence is strangely capable of returning my characters to reality and preparing them to accept their moment of grace. Their heads are so hard that almost nothing else will do the work. This idea, that reality is something to which we must be returned at considerable cost, is one which is seldom understood by the casual reader, but it is one which is implicit in the Christian view of the world.”

So violence is a means of getting both her readers’ and her characters’ attention. But, in addition to this, it is also a condition of our existence. Christianity is predicated upon a violent act. The crucifix is the central symbol of the Christian vision—and the Catholic crucifix, in particular, features the suffering body of a broken human being who is also, somehow, God. It is through this suffering and violence that the divine and the human are brought together, and all of this is bound up with love. This is a mystery that O’Connor embodies over and over in her stories. Of course, she is not alone in this. Many Christian and Catholic writers, from Dante onward—as well as Catholic practice (namely, the Eucharist)—feature violence as a means of redemption and conversion. It is a language she is steeped in as a Catholic.

Is there anything in particular that aspiring writers should pay attention to as they consider Flannery O’Connor’s life?

O’Connor was absolutely dedicated to her craft. She worked like someone who knew she had limited time to accomplish what she needed to accomplish. She wrote faithfully every day for two hours in the morning (all that her illness would allow her to do), and she sent her work out into the world, believing in its ultimate goodness, if not its perfection. I think this is a lesson for every writer. If you have a gift, you have to use it, no matter how difficult the circumstances.

I also love the fact that O’Connor was realistic but never cynical about the literary world or the world at large, for that matter. For all of her wry humor and her (sometimes) satiric vision, she loved the world and believed it to be the job of every artist to do the same. O’Connor once wrote, “You have to cherish the world at the same time you struggle to endure it.” This line is a truth about the world for the ages, under any circumstances, but it becomes especially poignant when we consider Flannery’s. Unremarkable and, at times, downright ugly as it may seem, the world is full of revelations of God’s love, if only we would learn how to receive them. And any writer would do well to teach the reader to cherish the world as dearly as she does.

Thank you for this interview. I feel I have a new appreciation for Flannery O’Connor’s gifts to the world of literature.

Thanks for this interview, Elisabeth. Interesting thoughts on the use of violence and the grotesque in fiction that cannot assume shared religious knowledge or sentiment. O’Connor has always inspired.

This rarity of a lady is a testiment to G-d’s generous blessings to all of us. (She never plagerized, either.)