Grandma Katie, my paternal great-grandmother, lived about three blocks from my childhood church and her home was a frequent destination for my mother and me on Sundays after the service. Upon arrival, she’d offer us something to eat. No matter what we said, there was going to be a plate of food placed before us. Jambalaya. Red beans and rice. Greens. Potato salad. Whatever she was fixing for dinner or had as leftovers would be consumed before we left.

I can’t remember if she was a good cook or not, because my favorite meal she made wasn’t even cooked. Yet it makes my mouth water as I type these words: sardines, saltine crackers, and tomatoes from her garden sprinkled with a pinch of salt and pepper.

Simple and elegant.

I don’t know how many cans of sardines, boxes of crackers, and pounds of tomatoes my mom and I savored sitting at Grandma Katie’s kitchen table. Even if that’s all she had in her pantry, she always had enough, regardless of who showed up at her door.

To earn her living, Grandma Katie cleaned the house of a wealthy white family in the Berkeley hills, adjacent to the University of California. On occasion, I’d accompany her to work. As she labored for the parents, I played with their children. I never felt any shame or a sense of being less-than, but it was very clear that I was now in another place. A place where the beans and rice were a side-dish accompanying the meat. Where I was from the meat, if there was any, was a flavor enhancer.

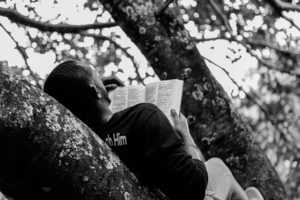

I don’t remember ever attending church with Grandma Katie, although I do recall our many trips to the racetrack. Our bets were placed in increments of nickels, dimes, and quarters, and the winnings, if any, were safeguarded in a purple velvet satchel with gold stitching embossed with the words “Crown Royal.” While I wasn’t cognizant of it at the time, and am still wrestling with understanding it today, the time I spent with Grandma Katie, and the other matriarchs of my family—Grammy, Nana, and Dear—were fundamental to my faith formation and spiritual development. Despite seldom, if ever, worshiping with any of them in a “traditional” setting, I knew they were aware of the Divine in their lives. More than the God-talk peppering their speech, I noticed that in the periodic lulls of busy days or at the conclusion of their labors, they would retreat to a quiet corner and read the Bible or with closed eyes bow their heads and whisper softly to themselves.

The time I spent with Grandma Katie, and the other matriarchs of my family—Grammy, Nana, and Dear—were fundamental to my faith formation and spiritual development.

I have those Bibles. One sits on my nightstand and the others are in my office. I refer to them often in the course of my divinity school studies. Turning those dog-eared pages and reading the highlighted passages has not only deepened my understanding of what scripture says, but more importantly, how it was contextualized and expressed in the lives of my ancestors. Their Blackness, womanhood, lack of formal education, and subsistence wages garnered as domestic and clerical workers may have consigned them to the sidelines of a society that did not see God in them. But like many of the women in the Bible, my grandmothers and great-grandmothers, saw in themselves (and in me) God’s promise. They may have been responsible to set the table, but they would never have a seat at the table they served. So, they used their sophisticated sass to make something sustaining and fulfilling from the crumbs that fell to the floor.

I am ashamed I once rejected Christianity as the white man’s religion. I did so without even considering that my ancestors had their own ways of thinking about God, even though examples were right in front of me. I did not question the notion the enslaved community became Christians under duress, or dare to imagine they embraced and practiced Christianity because in Jesus they saw a model of revolutionary service and love that could bring about an earthly salvation, if not for themselves, then for generations to come. I had moved to a different place. I did not require steak with my beans and rice, but I also could not see how satisfying and strengthening a couple of pieces of fish and bread could be in feeding the soul of a people.

I am ashamed I once rejected Christianity as the white man’s religion. I did so without even considering that my ancestors had their own ways of thinking about God, even though examples were right in front of me.

I eventually returned to Grandma Katie’s table many years later with the realization that the faith of my ancestors could nourish and sustain generations to come. It’s a faith that gave them the gumption to believe that a patch of land on a grimy street in West Oakland half the size of my office desk could yield an endless bounty of tomatoes. It is a faith that has been and continues to be at odds with the enslavers of antebellum America and their descendants today.

There is very little that distinguishes Black Protestants and white Evangelical Protestants in terms of religious beliefs and practices. While the racial make-up of the congregations differs sharply, each Sunday they often sing the same songs from the same hymnals—albeit to slightly different rhythms. Yet, when it comes to how their beliefs as Christians are put into practice or expressed in the public square, they couldn’t be further apart.

While both profess a belief in the same Jesus, the interpretive lens they apply to how they are called to live their lives in communion with all of humanity is wholly other. They are so different, I often wonder if the God Black and white Christians worship from our respective altars is in fact the same God. It frightens me to think these thoughts let alone express them out loud, but true reconciliation and redemption as Christians will never be fulfilled if we mask our innermost thoughts and feelings.

I thought about this after a recent trip to the Museum of the Bible in Washington, DC, with my classmates from the Howard University School of Divinity, which left me shaken and disturbed. I didn’t know what to expect as I entered the building. Everywhere I looked, there were dazzling visual displays that were slightly hypnotic. I asked one of my classmates, who had been to the museum several times, where I should begin. He said, “The top. I think that’s where they want you to start and then work your way down.” This made me laugh, because the National Museum of African American History and Culture, where we were supposed to be that morning, has you start at the bottom and work your way up.

Walking through the museum, I was in awe of the use of technology and multimedia to craft a narrative and compellingly tell a story. But I didn’t realize my intellectual antenna had been dulled because of all the entertaining stimuli. I was sleep-walking.

I came awake during the Hebrew Bible Experience, when I noticed Hagar was missing from the story of Abraham. Hagar was an enslaved African, who was given to Abraham by his wife Sarah for sexual servitude in order to fulfill God’s promise of fatherhood. Hagar gives birth to Ishmael, but mother and child are ultimately cast into the wilderness after Isaac is born to Sarah. As the son of a single mother, the story of Hagar and Ishmael has always had a strong allure for me. Her absence jolted me from my slumber.

I came awake during the Hebrew Bible Experience, when I noticed Hagar was missing from the story of Abraham. Hagar was an enslaved African, who was given to Abraham by his wife Sarah for sexual servitude in order to fulfill God’s promise of fatherhood. Hagar gives birth to Ishmael, but mother and child are ultimately cast into the wilderness after Isaac is born to Sarah. As the son of a single mother, the story of Hagar and Ishmael has always had a strong allure for me. Her absence jolted me from my slumber.

If you can’t see Hagar in the biblical narrative, you will never see the Hagars we encounter as we move through life. If you can’t see her, you can never identify with her pain, sorrow, and yearning to be free, not just for herself but for her unborn child and those of others.

The theological lens of Black Christianity not only sees Hagar but is framed by her gaze. Hagar is not looking for a handout, but rather a hand up into the fullness of what God intends for humanity. Black Christianity was developed to be a counterforce against the exploitation and oppression of people and natural resources. Drawing upon African spiritual and religious traditions, including Islam, the enslaved community embraced Christianity because they heard a message tailor-made for them. They didn’t just see Hagar. They knew Hagar because they were Hagar and like her, yearned to be free.

From the very beginning, Black Christianity developed as a revolutionary movement to liberate the mind, body, and soul. It provides a helpful prophetic toolbox for sacred and secular concerns, regardless of electoral outcomes. It is a faith that is designed to withstand the whims of politics because it is based on a faith that existed before the horrors that terrorized my ancestors in this country, while drawing on and being shaped by the liberating ministry of Jesus.

From the very beginning, Black Christianity developed as a revolutionary movement to liberate the mind, body, and soul.

I am reminded of this every time I eat sardines, saltine crackers and tomatoes sprinkled with a pinch of salt and pepper.

Like this post? Subscribe to have new posts sent to you by email the same day they are posted.

This essay is brilliant, and superbly crafted. “Black Christianity … provides a helpful prophetic toolbox for sacred and secular concerns.” That’s the program for a book you need to write in honor/memory of Grandma Katie, with a picture of sardines, crackers, and tomatoes on the cover.

Good Account, Jioni.

Jioni, I absolutely loved your family story regarding your matriarch and the comparison to Hagar. When you mentioned Hagar I thought about myself, a black woman in society, as a Hagar. Viewed as second to white women, discarded when determined as a threat or no longer needed; faith-filled and extremely grateful when God increases the territory of my son’s lives after society attempts to make them irrelevant. And God makes a way after no way, every time. Thank you for your inspirational work highlighting the power of the Hagar story and your generations of grandmothers.