I stood beside an Indigenous man, an artist born on an Ontario First Nation. He was, oddly enough, wearing an Amish straw hat. I asked him about the prints he had displayed on the table in front of us. I could see the connection in his work to that of the widely-celebrated Ojibwa artist Norval Morriseau. He seemed pleased when I mentioned it. The story of the artist I was talking with, the little I know of it at least, is worth telling. But it’s not my story to tell. Our conversation drifted to the link he and I shared: his people had been sent to institutions known as Indian Residential Schools; my people had run them.

In Canada the term “residential school” usually applies to government-sponsored institutions set up to forcibly assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian society. At its peak, in the early decades of the twentieth century, the residential school system included some 80 schools. At any particular time as many as one-third of school-age Indigenous children attended these schools, and more than 3,000 children died at them. Many of these deaths resulted from disease to which overcrowding and malnutrition made the children particularly susceptible. The system has come to be symbolized by the words of Duncan Campbell Scott, head of the Department of Indian Affairs, who, in 1920, said, “our object is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic.” Residential schools were a means toward that end. Early in the venture, the Canadian government realized that getting churches to run these schools represented a financial and pedagogical shortcut to meeting their treaty obligations. Churches, most notably Roman Catholic, Anglican, and those that would later form the United Church of Canada, saw the project as a missionary opportunity that came with financial support from the federal government.

Mennonite involvement—I am a Mennonite pastor—was relatively minor and, until recently, little known. Apparently some Mennonites who were conscientious objectors to military service taught in schools run by other churches, especially during times of war. Mennonites also ran three schools in western Ontario from the early 1960s through 1990. None of the schools were administered or directly sponsored by a denominational network. Instead, they were run by independent mission organizations, mainly connected with conservative or, better put, culturally distinct Mennonite communities. These particular Mennonites tried to dress and act in ways that differentiated themselves from their non-Mennonite neighbors. Many of the men wore what they called “plain suites” with jackets that lacked lapels, and many of the women wore long dresses and a “covering,” a piece of lace fabric pinned over their hair. Financial support along with volunteer staff and construction workers came from these types of churches in the US and southern Ontario. Many early volunteers were young American men who had been drafted for military duty but chose to do alternative service in line with their pacifist beliefs. Their opportunity to do alternative service in the north was facilitated by a Mennonite relief and development agency that had a broad agreement with the U.S. government allowing such international assignments.

The reports of former students at these Mennonite residential schools are as mixed as one might expect. Many staff were kind. Many students went on to assume key leadership positions in First Nations communities and beyond. Nevertheless, the overwhelming experience was negative. Many former students, who are also called “residential school survivors,” report that they experienced a profound sense of cultural dislocation, loneliness, an undermining of their Indigenous identity and, in some cases, harsh corporal punishment. One man who attended the Poplar Hill school in the 1980s recalled the indignity of having his long hair cut and being automatically treated for lice. Students and their families had to request admission to these schools. Even so, another former student remembers seeing an airplane arrive at her village and a young child, who was clinging to her mother, being forcibly taken by a Mennonite pilot.

In 1997, two key figures in the establishment of these schools published an apologetic letter in a northern-Ontario newspaper. They said that they were drawn to participate in the residential school system without ever having visited such a school. They said that they did not realize the extent to which cultures clashed in these institutions. In their letter, the two early leaders asked whether the schools should have ever been started. Their answer was “no.”

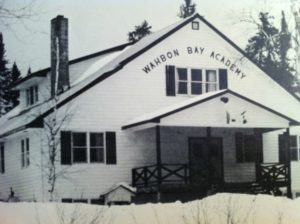

Wahbon Bay Academy where the author’s parents were on staff. Photo courtesy of author.

My picture is in the yearbooks of some of these schools. I am not with the students, but on the pages featuring staff families. I was just a kid. Like most kids, I don’t think I felt that the situation in which I was growing up was particularly strange. Yet it’s this connection that I share with the artist. If I didn’t have more serious questions for him, I probably would have asked him about the Amish hat. We were in Amish country, so maybe he was being culturally sensitive. Or maybe he was exposing the way white folks like to pick up tokens of other cultures. He may have seen his share of dream-catchers pulled through traffic by rearview mirrors framing Euro-Canadian faces. Or maybe not.

As I looked at the man’s art, I couldn’t ignore the fact that I am linked with a national attempt to wipe out his culture. I’ve talked to enough former Mennonite residential school staff to know that few, if any, understood the political context in which their younger selves had acted. They had believed they were providing Indigenous families with a good alternative to shipping their kids off to school in the city. The Mennonite schools were deliberately placed in remote northern locations to keep the students closer to home. At various times the schools had Native Advisory Boards. And yet the staff wielded power they probably never thought about. The world of English, the world of tight schedules, the world of stringent discipline—that was a Euro-Canadian world. One former staff member told me with remorse of the way a young student was harshly chastised for peeing behind a tree instead of in the facilities provided.

I’ve read many of the old letters the mission agencies sent to their supporters. They seemed sincere in their attempts to “improve” the lives their Indigenous students. Many staff sacrificed comfort and pay to serve as they did. And yet they were complicit. Probably naïve, but still complicit. If you know anything about Mennonite Christians, you may know that historically ours is a minority tradition, a tradition rooted in martyrdom. We do not always realize the power of our own cultural connections or the power of skin color.

I cannot help but think that peace is complicated business. In northern Ontario young men served in remote locations with little or no pay so they would not have to kill on the far side of the Pacific. They believed they were trading a destructive calling for a constructive one. It is not uncommon to have the wisdom of one age overturned by the wisdom of the next. What is less common is to have it happen so quickly. Many of the former staff I talk to are now hesitant to even speak about their work in the north. The narrative that surrounds their lives has changed. Once celebrated as self-sacrificing examples of true faith, they are now indelibly tied to a national disgrace. While it’s true that not all residential schools were alike, the differences don’t show up on your resume.

As I reflect on this, my mind settles on two things—for the time-being at least. One is that I’m convinced more of us are complicit in more violence than we acknowledge. At the very least, the lives of those of us in rich countries perpetuate what Rob Nixon calls “slow violence” in poor countries. We don’t recognize the harm our way of life causes because it doesn’t happen all at once with a bomb-blast. But, slow or fast, the harm still happens. Secondly, I’ve come to recognize that the practice of confession in Christian worship is not merely a way to find some relief from the guilt over dumb things we do out of habit or lack of will. It is also a way to bring before God our involvement in things bigger than ourselves, our complicity in evil we did not comprehend and our failed best intentions.

At the artist’s table I chose a print in the Woodland style from a series called “Metamorphosis.” It is his vision of the future. I wonder if his curious hat symbolizes a prophet’s calling.

Like this post? Subscribe to have new posts sent to you by email the same day they are posted.

Thank you, Anthony, for these very moving and insightful pieces.

Appreciate the perspective here & in the article I just read that you wrote in January 2019.