As we celebrate our 50th Anniversary, Bearings Online is highlighting profiles of persons closely associated with Collegeville Institute’s history—that great cloud of witnesses who have accompanied us since 1967, and will journey with us into the future.

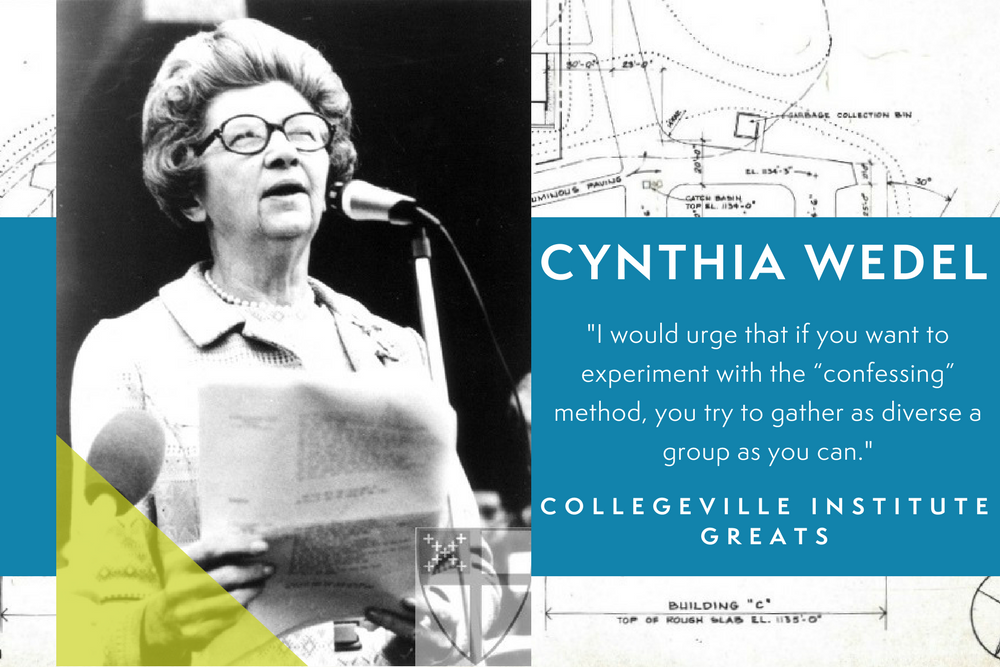

Cynthia Wedel was one of the most prominent ecumenical leaders in the U.S. in the 1950s and 1960s, referred to as “first lady of ecumenism” by the Christian Century. She was the first woman president of the National Council of Churches when she was elected in 1969 during one of the stormiest periods in the council’s history. Her election pitted her against militant black activist, Rev. Albert B. Cleage Jr., a United Church of Christ pastor and the author of The Black Messiah. At the time of her election, Wedel said the council “should have had a black president this year,” but noted that black moderates on the council could not accept a radical while the radicals would not accept a moderate.

Cynthia Wedel was one of the most prominent ecumenical leaders in the U.S. in the 1950s and 1960s, referred to as “first lady of ecumenism” by the Christian Century. She was the first woman president of the National Council of Churches when she was elected in 1969 during one of the stormiest periods in the council’s history. Her election pitted her against militant black activist, Rev. Albert B. Cleage Jr., a United Church of Christ pastor and the author of The Black Messiah. At the time of her election, Wedel said the council “should have had a black president this year,” but noted that black moderates on the council could not accept a radical while the radicals would not accept a moderate.

Wedel was not afraid to speak her mind. In their book The Episcopalians, David Hein and Gardiner H. Shattuck observe that, in an article written for the Christian Century’s “How My Mind has Changed” series, Wedel criticized “a new breed of clergymen,” who were committed to social activism, but at the same time were fundamentally “insensitive to the average man and woman in the pew.” The authors also note that Wedel “consistently supported the cause of women’s rights in the church, and with the rise of the movement for women’s ordination, argued that the presence of ordained women would greatly enhance the church’s understanding of ministry.” Wedel served as president of the council until 1972.

Wedel also served as a president of the World Council of Churches between 1975 and 1983, and as a president of United Church Women (now known as Church Women United) between 1965 and 1968. In the early 1960’s President John F. Kennedy appointed her to his administration’s Commission on the Status of Women. She was an official observer at Vatican II in 1965, and was the first woman to speak from the floor at the Lambeth Conference of Anglican Bishops.

Wedel is a Collegeville Institute Great because of her long and distinguished career dedicated to ecumenism, which included service on the Collegeville Institute’s Board of Directors. What follows is her reflection on her participation in the first of the Collegeville Institute’s summer consultations, “Confessing Faith in God Today.” This modified excerpt is from the foreword to God on Our Minds, by Patrick Henry and Thomas F. Stransky, CSP (Fortress Press and Liturgical Press, 1982). Her comments are significant for their reference to the first-person method, also known as the “Collegeville approach,” which was pioneered in such consultations at the Collegeville Institute and has been practiced there since 1976.

//

I spend my life in meetings and conferences of church groups and various organizations in which I am active. When I was invited to participate in the “Confessing Faith in God” project I agreed because I am a member of the Board of the Institute for Ecumenical and Cultural Research, and I don’t like token board members.

I went a little reluctantly. I had seen the list of participants. I had an idea of what it would be like—complex theological discussions using technical jargon which I understand poorly, and arguments over obscure points which mean very little to a lay person struggling to be a Christian. I have been around enough theologians to know that, like any professional group, they nearly always try to “one up” each other by having read the latest book in some foreign language. I didn’t expect to take much part in the discussions and I just hoped I could look interested and moderately intelligent.

What a surprise awaited me! The first meeting was a brief time of getting acquainted—putting names and faces together. Then we were to spend the next day alone, writing about our own experiences in relation to God. This was to be strictly autobiographical—no quoting of others, no theorizing, just telling of our own pilgrimage.

Our papers were collected and duplicated; then we met, and each one told her or his story, expanding on what was in the paper. Suddenly these formidable strangers were people—very human, often unsure and weak, sometimes joyous and confident. Many told of long wanderings in disbelief and a slow return to a new relationship with God. Some admitted to being still in the wilderness. No one quoted Tillich, Barth, Küng, or Rahner to score a point. We were speaking for ourselves. I began to understand why it had been called “Confessing Faith in God,” for we were indeed “confessing”—speaking out of our own past and present with their high and low points.

We were Roman Catholics, Orthodox, mainline and evangelical Protestants—black and white—men and women. Our journeys had been very different, yet we could feel ourselves living in each one. As we moved through several periods of time together, we all became convinced that one of the great needs of the church and of individual Christians today is to be jolted out of our routine experience of the faith, which so many of us practice with little critical thought, and to be brought back to the basis—God. I thought of the highly educated, competent lay persons I know whose understanding of their faith is still at a fourth-grade Sunday school level. And I thought too of the many ministers and priests who are so caught up in the busyness of congregational and parish life that they find little time for thought or reflection.

My own relationship with God is richer as a result of this experience. I would urge that if you want to experiment with the “confessing” method, you try to gather as diverse a group as you can. It will work, of course, even if you are all of the same age or sex or race or religious affiliation. But it will be far more effective if you are not.

Like this post? Subscribe to have new posts sent to you by email the same day they are posted.

Leave a Reply