This essay is a product of the Collegeville Institute’s Emerging Writers Mentorship Program, a 9-month program for writers who address matters of faith in their work. Each participant has the opportunity to publish their work at Bearings Online. Click here to read essays from past Emerging Writers Program cohorts. We are pleased to offer this essay by Ellen Rowse Spero on the first day of Passover and the even of the Easter Triduum.

On the third day of a summer course in Biblical Hebrew, I found myself in an intense encounter with God. Not with the familiar God I knew—the God I sense in the beauty of nature; the God of Love whom I trust embraces every human being with deep care. No, this was an unfamiliar side of God that I had not fully met before: ancient, almost frighteningly strange. Yet intimately present. Out of nowhere.

I was quietly relieved to be in the classroom again. I had taken seven months off from seminary after the birth of my son—an unexpected joy after nine years of trying unsuccessfully to have a child. But my pregnancy had been difficult, and I had struggled through the first couple months with my colicky baby. My family knew I was anxious to catch up with my credits and ordination requirements, so they pooled their resources to take care of my son for the six weeks of the course. I felt the pressure of their sacrifice to support me as well as that of learning a new language with a completely different alphabet in a compressed time frame. But when that third day came, I had no choice but to slow down and make room for something far more important than catching up on my studies.

I cannot forget what happened in that corner classroom.

Twenty-seven years have passed since then and I have forgotten almost everything I learned about Hebrew’s grammar and alphabet. I can barely recognize a few well-known words. But I cannot forget what happened in that corner classroom, as I sat with the seven other students at tables arranged in a horseshoe. With windows on two sides, the air-conditioning could barely compete with the heat of the D.C. summer. Our enthusiastic professor moved energetically as she led us through the material for the day’s lessons. She wrote quickly on the large white board, seamlessly switching back and forth between the two alphabets, left to right, right to left. She set such a swift pace to get us through the curriculum in our short time that I felt behind before we even started.

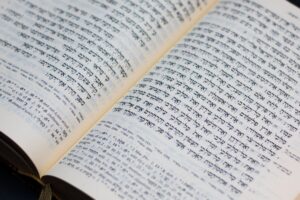

The immersion into a language whose alphabet and grammar were wholly different was disorienting in a way that learning French had not been. I had had a taste of this fourteen years before when I was visiting my grandmother in her suburban neighborhood in Israel. Trying to find my way back to her home, I looked up at the street signs and realized I could not decipher any of the letters. Now, after just two days with only a rudimentary grasp of the language, I was expected to read a text and translate it into English. With my laminated guide sheets for the alphabet and grammar and Holladay’s Concise Hebrew Lexicon next to my notebook, I took a deep breath to start my first translation.

The passage was Genesis 22, the Sacrifice of Isaac, called the Akedah in Hebrew, meaning “the binding.” All of us knew it well, having read it many times in English. Because I knew how it would turn out—that God would stay Abraham’s hand, saving Isaac at the last minute—I had always read through the terrible parts without concern because I knew Abraham and Isaac had nothing to fear. And therefore, neither did I. The God of this story felt distant and from long ago, and didn’t resonate with my more modern, comfortable experience of the Divine. But when I read the story in Hebrew, this all changed.

An ancient language, Hebrew had a smaller vocabulary than English (and modern Hebrew), using fewer words to do more, so that one root word could have several shades of meaning. It used anagrams, word play, and patterns to emphasize meaning in a sentence or story. With only two verb tenses, time worked in a way that was hard to render into English. Whole chunks of time—days, weeks, months, years—would be moved along in just a short phrase. Until it mattered: then time was slowed down by a growing intensity in the details of the narrative, the patterns of the words and phrases. I could never translate the awe and beauty I felt when the story shifted like this, from ordinary to sacred time.

I could never translate the awe and beauty I felt when the story shifted like this, from ordinary to sacred time.

I found myself slowly walking with Abraham—his conversations with God and with Isaac, the terrible journey of father and son up the mountain, the careful and agonizing preparations: “Abraham built an altar…” Step. “he laid out the wood…” Step. “he bound his son, Isaac…” Step. “he laid him on the altar…” Step. “on top of the wood…” Step. “And Abraham reached out his hand…” Step. “…and took the cleaver…” Step. “to slaughter his son.” Step. It was heartbreaking.

Abraham’s encounter with the God who commanded him to sacrifice his son, his only one, whom he loved, became my encounter too. It bound me closer to the God beyond my understanding. The God of the dark night of the soul, when prayers go unanswered and life is incomprehensible. The God of wildness, who cannot be tamed, cannot be bound in our image or to our will. The God who abided in the silence, then, in the story, and now, with me. I recognized this Divine presence—both awesome and intimate, not from my own experience, but in my DNA, inherited from generations before.

I encountered the God of my Jewish grandfather’s story in Abraham’s.

While I was raised Unitarian Universalist, my mother’s family is Jewish. I grew up with their stories about surviving World War II in Poland. I have lived my whole life aware that if not for a fragile string of coincidences, miracles and sacrifices that allowed my mother, my grandmother, and my great-grandmother to live, I would not exist. Nor would my son. I could trust in the God of love and hope because they were integral to my story of the blessing of life’s resilience. But then, there was my grandfather, whose story I know only a little: that he was a devout Jew, a physician, and that he did not survive. As I sat in that warm classroom, struggling to decipher this text, I was learning the language of my grandfather’s faith. His prayers. His conversations with God. I encountered the God of his story in Abraham’s.

“Do not reach your hand against the lad,” God’s messenger tells Abraham, as he lifts the cleaver to strike his blow, “for now I know that you fear God, and you have not held your son, your only one, from Me.” As I translated this line, I wondered in the silent spaces between the words if, after this ordeal, Abraham’s relationship with Isaac or with God was ever the same. I wondered, too, if this God was with my devoutly Jewish grandfather at his death in the cattle car taking him from Warsaw to Belzec. Part of me wonders why God did not in that moment or in so many others, stay the human hand of death and destruction. And a larger part of me hopes that God was there, even in God’s incomprehensible wildness, to accompany him in the silence of that last, terrifying journey so he would not be alone.

Like this post? Subscribe to have new posts sent to you by email the same day they are posted.

Leave a Reply