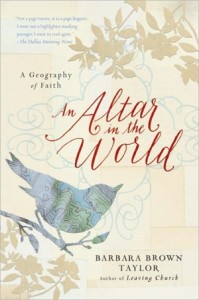

By Barbara Brown Taylor

Reviewed by Anne Apple

Writing Workshop Participant ’10

Harper Collins, 216 pp., $14.99

Barbara Brown Taylor uses two sets of questions to navigate her geography of faith: “What might you tell me about your life?” or “Who are you?” and “Where have you met the Divine in the ordinary moments of your life?” or “Whose are you?” The first set seems relatively simple. The second pushes more acutely into questions of faith. Piercing questions about self and faith have the momentum both to unleash longings for the more of deep connection and to teach us how to recognize the freedom that comes with self exploration.

These questions have taken Taylor, an Episcopal priest who has recently been named Georgia Memoir Writer of the Year, two books to answer. In the first, Leaving Church: A Memoir of Faith, Taylor describes the grief that accompanied her decision to leave parish ministry for a teaching position in the north Georgia mountains.

In the second, An Altar in the World: A Geography of Faith, she writes about the importance of paying attention to the ordinary if we are to live an engaged and authentic life. In 12 chapters, each focused on a particular spiritual practice, Taylor captures the heart of what it means to live with a willing intention to meet God in the ordinary places of life.

Taylor explores the questions she has set herself with a depth of intimacy and a dose of vulnerability that reveal what it means to be both authentically human and deeply connected to the Creator. She takes us to the intense intersection where crashes that disturb a numbed, inattentive way of living can occur.

In an early chapter, “The Practice of Wearing Skin,” Taylor tells a story about sharing good wine and conversation with a colleague. In a moment of audacious shared confession, assisted by the warmth of the wine, they talked about the bodily, visceral and sexual arousal that can come while praying and preaching. Accepting that God speaks through the tingle in the belly and the stirring of the soul is a dangerous, yet ancient, practice of trusting the love of the Creator. Taylor’s intensely sexual and intimate description of the practice of wearing skin has unfortunately led at least one church book group to put this book down and go no further.

Later in the same chapter Taylor describes the power of a group of clergy and lay people exploring the Beatitudes together. The group is told to bring a verse of scripture to bodily life in a wordless tableau. When the “blessed are those who mourn for they shall be comforted” group performed, their pose seemed overtly simple. One woman volunteered to “lie dead” and others gathered around – like most funeral visitations in the 21st century. The wordless exchange took an intense turn when the “dead woman’s” guttural and unexpected sob took the mourners by surprise and led to a collision of who and whose we are and an unexpected chorus of weeping. A simple drama exercise turned reading scripture into the practice of wearing skin.

This memoir is worth the read. Taylor’s intense imagery coupled with her theological reflection make this a book to recommend to others. It might be tempting for churches to relegate this memoir to the ranks of individual pietism, but it’s worth picking up and asking in a community, “Who are we?” and “Whose are we?”

I once heard Cornell West, a Princeton professor and author of Race Matters preach at a worship service hosted by the seminary where I teach, and I furiously scribbled notes. In the context of his sermon unfolding what Job’s words “naked I came from my mother’s womb and naked I shall return” meant, West boisterously implored, “People, don’t you get it? The church is failing as the people of God. We are failing to teach what it means to be human. We get all wrapped up in ourselves and forget the words at the beginning of our story, ‘You are dust, and to dust you shall return’.”

He went on, “Being human means we are a people getting low, getting close to the ground, living while knowing that we are creatures for burying. If it weren’t for our mother’s push we wouldn’t be here. We have to be the church living and working through all our messy humanness and not covering it up!”

Taylor’s memoir does just that. It challenges the church and its people to wake up to God, to live with purpose, to get lost while wearing skin and walking the earth. It charges the church and its people to practice saying ‘No’. It urges them not to be numb, but to practice feeling pain, to practice being present to God and to shower the world with the blessings of being fully human. Taylor’s memoir challenges us to be real and genuine, and to know who and whose we are.

As a pastor and mother, teacher and preacher, I find myself with both the living and the dying. Images from Taylor’s stories linger and haunt me with the whisper of the spirit and the courage to embrace my own humanity while serving the church. The curriculum review committee where I teach chose not to use this memoir in a formation for ministry class because it does not speak directly to the pastoral life within the institutional church.

Now I would more readily disagree with that decision. I would suggest that Taylor’s gift for writing and time spent in ministry allows her to present a subtle critique of the institutional church and to issue a challenge to the body of Christ. To be the body, we have to live in the body, practicing fleshy disciplines and nourishing our ability to perceive the beauty to be found in the altars of God’s world.

Anne Apple is Interim Associate Pastor for Congregational Life at Idlewild Presbyterian Church in Memphis, Tennessee. Anne attended Collegeville Institute’s summer writing workshops Writing for the Congregational Life in 2008 and Apart, and yet a Part in 2010.

Like this post? Subscribe to have new posts sent to you by email the same day they are posted.

Leave a Reply